Ask Good Questions

Poor election polling, noisy data, and the need for good questions in an age of information abundance.

Hey there! Quick request before we get started. As I’m preparing for my upcoming book, I wanted to take a quick poll to see where my readers live. If you don’t mind, could you please take five seconds to click the link below and add the name of the country you live in? Thanks! - Jack

In case you missed it earlier this week, there was a presidential election in the US of A. This election was particularly interesting for a few reasons:

The previous election had an insanely high voter turnout with 158 million total votes cast, including 81 million for Joe Biden. It was America’s highest voter turnout by percentage since 1900.

Trump was running for a nonconsecutive second term, which we hadn’t seen since Grover Cleveland in the 1890s.

Kamala Harris’s presidential campaign was only 108 days, as Joe Biden withdrew from the race on July 21.

Prediction markets emerged as an interesting foil to traditional polling, first with Polymarket overseas, and later with Kalshi, Robinhood, and Interactive Brokers in the US after a federal judge ruled in Kalshi’s favor over a CFTC attempt to block election markets.

The last point proved to be especially important. Most polls, from Nate Silver to The New York Times, showed Harris with a ~1 point lead heading into Tuesday, and they considered the election a ~50/50 shot that could go either way. Silver even ran 80,000 simulations, just to determine that the outcome of the election would, basically, come down to a coin flip. God, I love statisticians. A thousand complex models just to say “maybe.” It’s incredible.

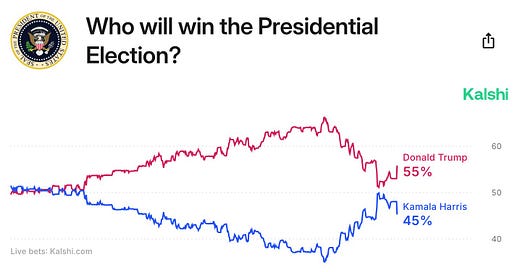

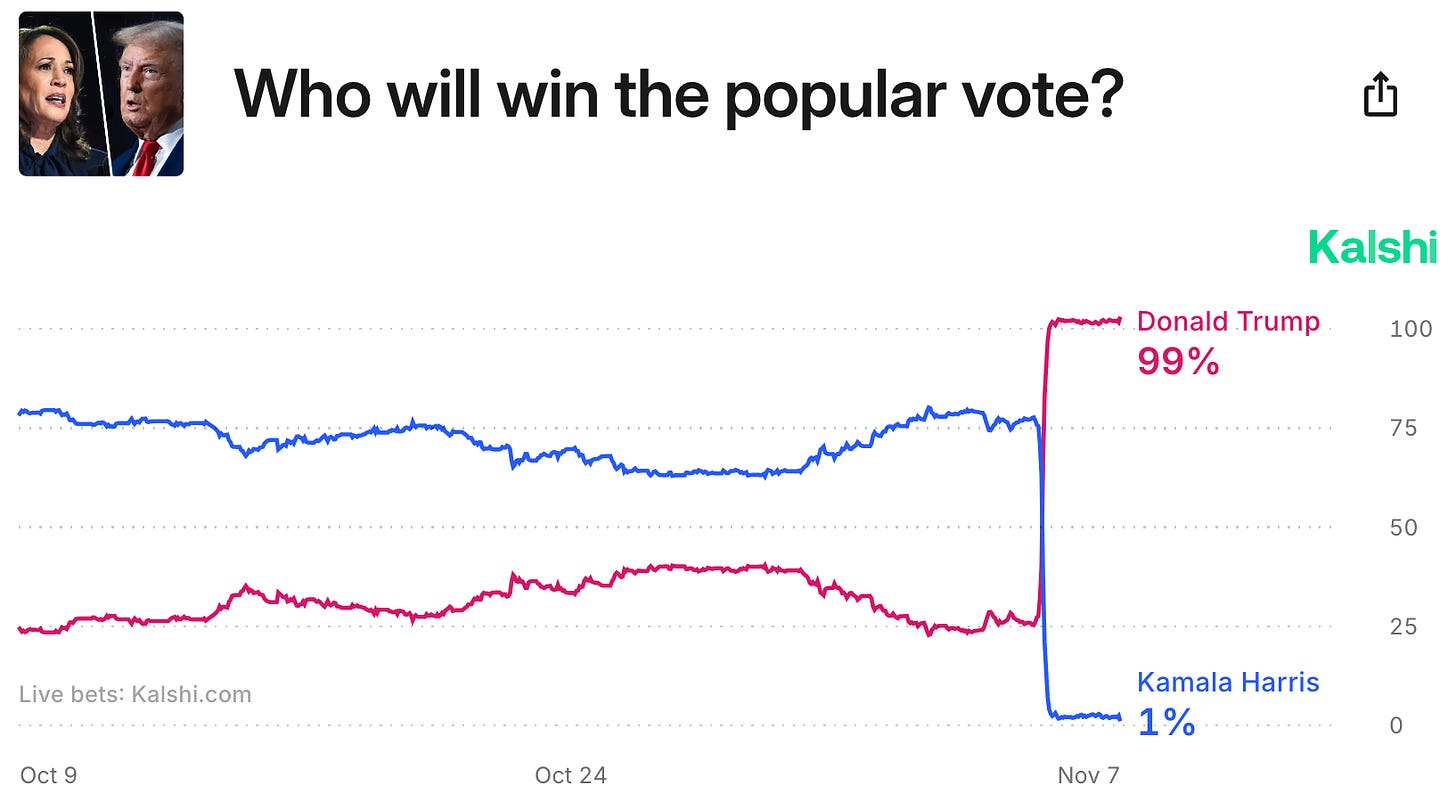

Meanwhile, prediction markets like Polymarket and Kalshi showed Trump ahead by a sizable margin for the month leading up to the election. The day before the election, While the Times showed Harris with a 1 point lead, Kalshi had Trump up by 10 points:

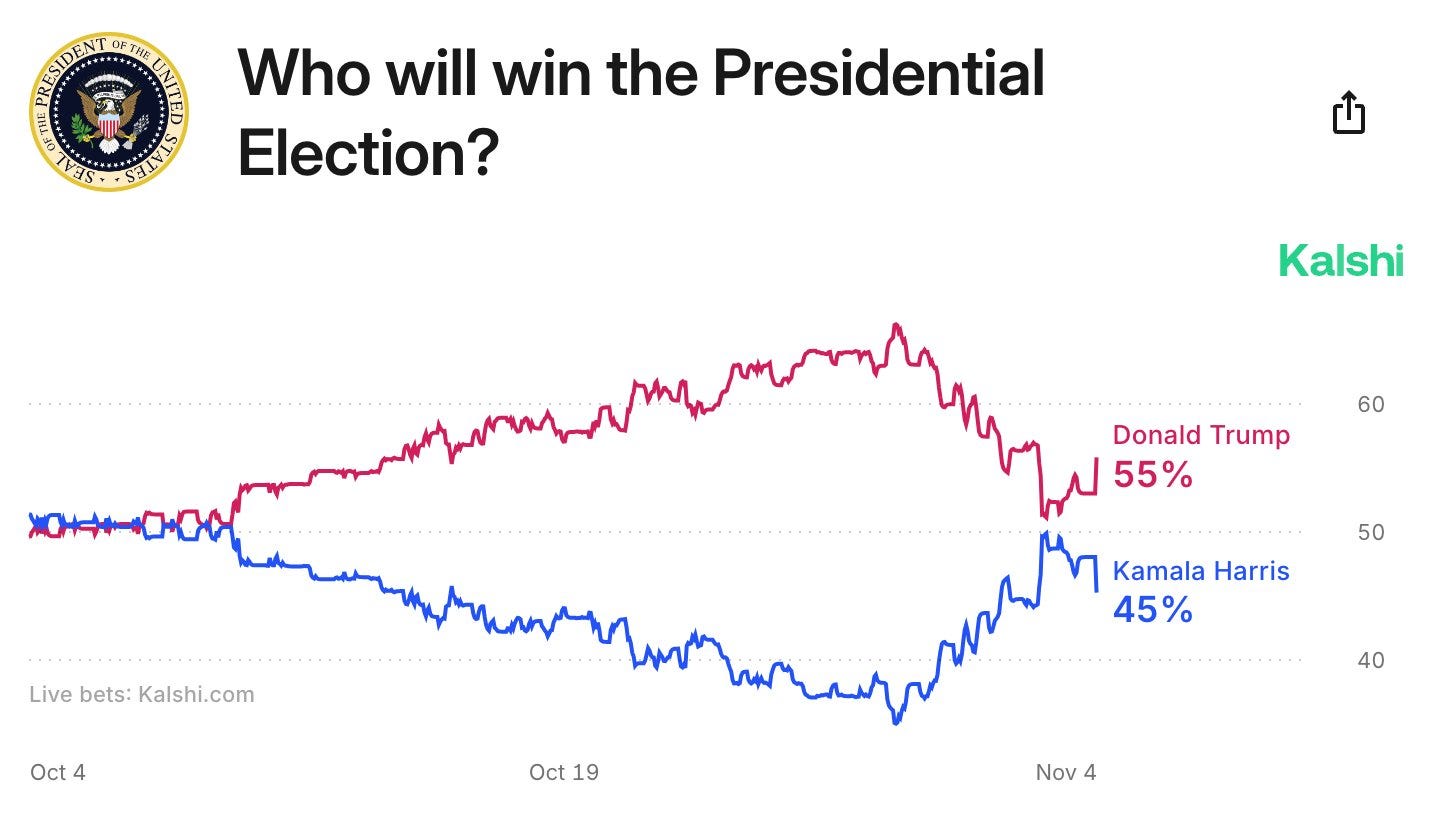

Something had to give, and as we found out Tuesday, that something was the polls. Trump didn’t just win a coin flip, the election was a landslide that saw him winning the popular vote, which no one, including prediction markets, expected:

My question, when I woke up Wednesday, was this: How did the polls get it so wrong? After all, we had access to more information for this election than we’ve ever had before:

County and state voting data for two election cycles involving Trump and one involving Harris.

24/7 sentiment analysis via social media platforms like TikTok and X.

Frequent face-to-face interactions between voters (vs. 2020, when lockdowns were rampant) that would help folks get a feel for how their peers were voting.

And yet, despite this abundance of information and data, the polls missed the mark. Bad. And it wasn’t just the polls that got surprised! I had dozens of conversations with friends on both sides of the aisle leading up to the election, and everyone, regardless of party allegiance, said they had no idea which way the election would go. As of five days ago, I thought Trump was cooked. And yet, he had basically won the election by 10 PM Tuesday night.

How was everyone so far off?

One reason, I think, is that this abundance of information proved to be distracting, rather than insightful. If you spent 45 minutes on Twitter before the election, you would have thought that Trump was winning 90% of the popular vote. If you then switched over to Threads, you would have thought the opposite. Had you asked an NYU student (other than a 6’9 freshman named Barron), they would have been shocked that anyone was voting for Trump. Ask a mechanic in rural Ohio, and they would tell you that a vote for Harris is a vote for communism.

Had you asked any individual who they were voting for, there’s a chance that they would have answered with the answer that they thought they should say, rather than their actual opinion. You could have Googled all sorts of stats to help you forecast the election, from previous polling data to state-to-state migration patterns that might impact electoral college votes, if you so fancied. My point is that you could have taken a near-infinite number of approaches to determining which way the election might go, so it’s no surprise that no one had any idea.

Except some French dude named “Théo.”

One of the more intriguing stories to emerge from the prediction market arc was the “Trump whale,” a mystery Polymarket trader who wagered ~$30 million across various bets predicting that Trump would win the election.

This trader, a French dude who called himself “Théo,” told The Wall Street Journal that he had “absolutely no political agenda.” He simply thought the polls were underrepresenting Trump as they had done in 2016 and 2020, he believed Trump’s odds were higher than markets were assuming, and he decided to put some money behind that belief.

(This money turned out to be the majority of his liquid assets. He also went by the psuedonym “Théo” for his Journal interview because he hadn’t told friends and children about the bet, and he didn’t want them to know the extent of his wealth. The whole thing is honestly pretty based).

However, the Frenchman didn’t just YOLO his life’s savings on vibes. He took a novel approach to verifying his thesis:

Polls failed to account for the “shy Trump voter effect,” Théo said. Either Trump backers were reluctant to tell pollsters that they supported the former president, or they didn’t want to participate in polls, Théo wrote.

To solve this problem, Théo argued that pollsters should use what are known as neighbor polls that ask respondents which candidates they expect their neighbors to support. The idea is that people might not want to reveal their own preferences, but will indirectly reveal them when asked to guess who their neighbors plan to vote for…

In an email, he told the Journal that he had commissioned his own surveys to measure the neighbor effect, using a major pollster whom he declined to name. The results, he wrote, “were mind blowing to the favor of Trump!”

Théo declined to share those surveys, saying his agreement with the pollster required him to keep the results private. But he argued that U.S. pollsters should use the neighbor method in future surveys to avoid another embarrassing miss.

“Public opinion would have been better prepared if the latest polls had measured that neighbor effect,” Théo said.

The reason that Théo found valuable, actionable information was that he asked the right question: How are your neighbors voting?

The internet commoditized information, and the widespread availability of information has devalued it because you can now find some data point, anecdote, or statistic to support any possible viewpoint, creating an environment ripe for echo chambers and false signals, which we saw this election cycle.

To cut through those false signals, you have to be careful in deciding which information to look for. You have to ask good questions. The polls made the mistake of asking the folks they were surveying who they were voting for, not accounting for inaccurate responses. As a result, they got faulty information. Théo’s method, asking who “your neighbors” are voting for, proved to be more accurate, as it reduced the risk that someone would change their answer to save face.

Of course, this dynamic applies to so much more than presidential elections. If you’re trying to decide if you’re bullish or bearish on a stock, you’ll find a million arguments supporting both stances. (Don’t believe me? Google “Is Tesla undervalued?” then switch “undervalued” for “overvalued”). If you ask a dozen people what you should do with your career, you’ll get a dozen different answers. If you have a headache, you are only three WebMD searches away from convincing yourself that you’re having an aneurysm.

Our information overload is only going to get worse, too. Up until now, our main issue was that the cost of finding information had declined to zero. Thanks to generative AI tools, the cost of creating information has dropped to zero as well, and we’re in the early innings of an explosion in more data, more noise, and more content.

The antidote to this abundance of information is distillation: figuring out which information is important and discarding the rest. But distillation is downstream of interrogation: if you ask the right questions, the information filters itself.

- Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Jack's Picks

The Wall Street Journal’s recent piece on the French trader that made $80 million on his Trump Polymarket bet is fantastic.

The New York Times published a good article explaining how Intel fell behind in the AI chip boom.

I enjoyed this profile in The Atlantic on Mike Solana, the founder of Pirate Wires and the CMO of Founders Fund.

Sounds like by remaining anonymous from his friends and family Théo is the living proof of his own neighbor hypothesis lol

The most powerful part of your landing here is that distraction is going to increase, it's not going away. For those leaders who aren't self aware and have no one to tell them what their blind spots are, they're going to be left out of the game of success. Today, success is a game of devotion, attention and ACTION. LOVE the idea of engaging people (neighbors) to find out real data. Asking questions is a great start. In order to learn from the answers we get (to those questions) we need to be engaged in richer conversations. This election sucked the air from rich conversations. My prayer is that we've learned from this election to reinvent how we engage with the abundance of information we have to make more progress together.