Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

People typically buy an asset, whether it be a stock, bond, real estate, cryptocurrency, commodity future, or NFT, because they believe that at some point in the future, they will make money from their purchase. Time horizons, asset classes, and risk tolerances change, but no one in the history of financial markets has ever happily invested in something thinking, “Man, I cannot WAIT to lose money on this.”

Of course, we don’t make money on every purchase. In fact, sometimes we actually lose money on our investments. Maybe you purchased Meta stock before its stock price was cut in half as the company's revenue growth slowed. Maybe you invested in Zoom at the peak of Covid, only to see valuation compression wreck your investment. Maybe you paid $1.2M for a JPEG of a rock, and now you’re selling plasma to pay rent. Personally, I lost $157,000 by investing in a Buy Now, Pay Later company after its SPAC merger.

I don’t know, we all have our stories of losing money. And just as we all have our stories of losing money, we all had our reasons for making the investments that cost us money.

Maybe you bought bitcoin because you thought it would be an inflation hedge. Maybe you bought a Buy Now, Pay Later company called Katapult because you thought its valuation gap with its competitors would close (to be fair, the gap did close. Just not in the direction that I had predicted). Maybe you invested in Lululemon because you thought yoga pants marked a paradigm shift in the female wardrobe.

Whatever. The thesis doesn’t matter. You buy something because you think something else will happen. Then that thing does or doesn’t happen, and you may or may not make money as a result.

I’m going to discuss what happens when we “may not make money” in a minute, but first, a bit of context.

I’m only 25 years old, so I have no idea what investing was like 25, or 50, or 75 years ago. I do know that right now, in the era of social media and sensationalized television and the gamification of the stock market, tribalism has infected finance.

We are social creatures not all-that-far removed from our days spent in hunter-gatherer societies, and tribalism is a deeply entrenched part of human nature. We root for sports teams, participate in different religions, and align with political parties in the name of tribalism. We want to be in a “group.”

Before social media, money was a private matter. Maybe you discussed your finances with your spouse, a financial advisor, or a small group of friends, but you couldn’t advertise your bullishness on a stock to 100,000 strangers. But now, in the age of Twitter and Discord and TikTok, you can both broadcast your opinion AND find like-minded folks who share your opinion, too. Suddenly, finance became the newest medium for tribalism.

And people like identifying with their tribes. Tom Brady, Kevin O’Leary, and team bitcoin all threw laser eyes in their Twitter profile pictures as they rooted for it to reach $100,000. Tesla investors use the $TSLA tag on Twitter to publish their thoughts, and they gather in Twitter Spaces to listen to Elon discuss the status of the company. Pictures of slime-covered apes littered social media as folks who chose to buy a cartoon graphic of a primate instead of making a down payment on a house wanted to flex their digital wealth. Thousands of ‘investors’ formed a subreddit called “AMC Stock” where they echo conspiracy theories about the illuminati, Joe Biden, and Citadel’s Ken Griffin secretly using synthetic shares to artificially suppress the stock price of a mismanaged theater chain.

I have no idea what any of the words in the last sentence mean, but if you check out that web forum you'll see that I'm not far off.

And the better that the stock performs, the louder these tribes grow. When Bitcoin was on its meteoric rise to $69,000, there were enough laser eyes on Twitter to melt the polar ice caps. As Tesla eclipsed a $1T market capitalization, any and every critique, such as "perhaps it’s unreasonable for a car company to be worth $1T?" was met with a tsunami of backlash from the newly-rich EVangelists (see what I did there?)

“I like the stock” and "Buy the dip" replaced “Happy Birthday, B*tch” on bottle girls’ signs in Miami nightclubs, and investing became the new, hot social domain where those invested in the hottest assets were cool, and those who abstained could have fun staying poor.

And then Jerome Powell decided that perhaps interest rates shouldn’t remain at 0% forever and suddenly, when Treasury Bills are paying 4% risk-free returns, the net present value of the future cash flows of Dogecoin doesn't look so appealing, and the most speculative areas of the market entered free fall.

And now we’re in the “not making money part.”

I've noticed a pattern in financial markets over the past few years:

if your paper net worth increased by a factor of 10, 20, or 100 due to you investing in a speculative asset, and you found a community of likeminded investors who also got rich from the same speculative asset, and you loudly proclaimed to the world how much you love that speculative asset… well, that speculative asset likely became a core part of your identity.

And when you identify with that speculative asset, and that speculative asset starts looking like a speculative liability, you face a choice:

Do you sell to preserve your capital, or do you HODL to preserve your identity?

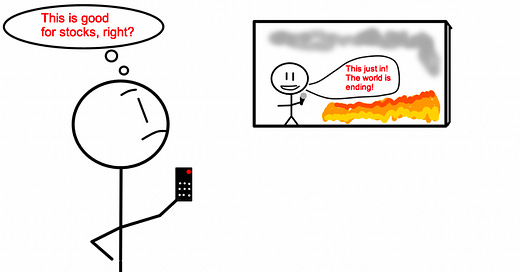

Of course, the rational decision is to sell, retain your capital, and find another investment opportunity. But irrational investments rarely end with rational exits. Instead of being rational, you rationalize.

“Oh, Tesla is cutting their prices by $12,000? That’s actually bullish for the stock because it means that they can undercut competition and increase their market share even more.”

“Bitcoin was an inflation hedge, it merely appreciated in value before inflation hit because it predicted the increase in money supply. This is its 4th super cycle, next time we’ll hit $100k.”

“Sure, AMC jumped from $3 to $50, but that wasn’t the real squeeze, the price is just being artificially suppressed.”

And in all of these cases, investors think, “We’re still so early.”

So instead of sticking with the thesis that initially got you interested in an asset, you mold your thesis to match your biases so you can justify continuing to hold your investment. Anything but admitting that you’re wrong.

Anything but losing part of your identity.

It is important to remember that investing serves one purpose: wealth creation. When your investment turns from wealth creator to wealth destroyer, it’s time to take a good, hard look at your portfolio. But the more you identify with your investment, the harder the breakup is going to be. Emotional bonds are difficult to sever, after all.

And that’s why we have seen, and will continue to see, so many go down with their ships. Or maybe the market is simply wrong. We’re still so early, right?

- Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!

Jack's Picks

Trung Phan wrote an interesting piece on why Netflix pays so much for top talent.

Semafor's Ben Smith covered the decline in billionaire-owned media.