Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

A surprising benefit of having my income largely tied to my Twitter activity is that over the last couple of years, I have met some really, really interesting folks on Twitter: writers, podcasters, entrepreneurs, investors, athletes, researchers, anonymous meme page shitposters, and everything in between.

A surprising benefit of moving to New York is that I now live in the same city as many of these Twitter connections, and I have met ~25 of them in real life since August.

A surprising benefit of meeting ~25 Twitter connections in real life is that I now consider a few of them to be good friends.

One of those friends is my man Connor Gross. Last Sunday, Connor blessed my timeline with this damning indictment of hustle culture content.

The irony of this tweet is that Connor is in the top 0.1% of 25-year-olds in terms of “crushing it.” He has built successful e-commerce brands, manages a growing real estate portfolio, and launched a newsletter and podcast to connect with other people doing cool stuff.

Meanwhile, most of the folks peddling the generic grindset garbage that Connor referred to are likely chilling in a lower tax bracket.

While his whole tweet is a banger, the penultimate sentence stood out to me: There’s a huge audience of people out there who are extremely good at making a ton of money… and still able to party, travel, stay in shape, be happy, etc.

And Connor’s right.

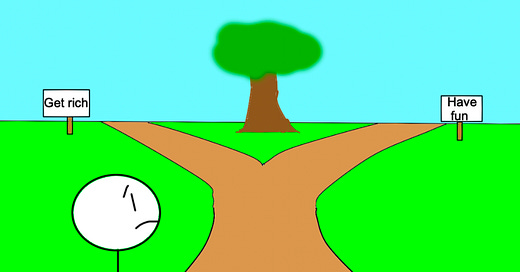

There’s this idea, especially early in our careers, that you can either choose money or fun (with fun being a subjective term that represents alternative activities to “work”), but you can’t have it both ways.

So we get stuck at this crossroads thinking, “Shit, now what?"

(The obvious answer, of course, is to go to business school, the only socially acceptable way to have carefree fun for two years and still get rewarded with a $200k salary after you graduate. I’m kidding. Kind of.)

And more often than not, in the face of uncertainty, we go left. But are these two options really mutually exclusive? I don’t know, let’s look at three examples of some relatively unknown entrepreneurs:

In his 20s, Steve Jobs spent months seeking spiritual enlightenment in India. After college, Jim Simons tried to ride a moped from Boston to Buenos Aires (though he was briefly detained in Mexico, and he only made it to Bogotá). At age 25, Phil Knight embarked on a year-long trip around the world.

It’s a damn shame that Jobs, Simons, and Knight didn’t spend every moment of their early adult lives grinding out 90-hour weeks. If they had, they might have achieved some semblance of success in their careers.

Let’s step away from these three well-known examples and get more granular. One of my favorite more recent examples of someone crushing it in all aspects of life is Bill Perkins.

Perkins spent the first 20 years of his career as an energy trader before launching his own hedge fund, Skylar Capital, in 2012. Last year, thanks to savvy trading in a turbulent energy market, Perkins’ fund booked a 208% return, and they now manage $500M in assets.

So yeah, you can say that Bill Perkins is a pretty successful dude.

But Perkins’ entire life isn’t dedicated to the market; far from it. Bill is also a professional poker player whose live tournament winnings have exceeded $5.4M, he has directed multiple Hollywood films, and his widely successful book, Die with Zero, has sold God-knows how many copies.

But Perkins isn’t just another anecdote supporting my hypothesis that success doesn’t have to be a one-dimensional pursuit. He is an outspoken proponent of this idea himself.

Throughout his book, he emphasizes that we should inject experiences and novel pursuits early and often to maximize our life satisfaction, a position that runs counter to the “all-in or bust” mindset.

The following are two references from Die with Zero. The first is a reference to Perkins’ thriftiness while working his first job, and the second is a story about his roommate’s decision to leave his job for three months to travel abroad.

So I started driving my boss’s limo at night to earn extra cash. And I became super-thrifty, trying to sock away as much savings as I could…

Then, one day, I was talking to my boss, Joe Farrell, a partner at the company I was working for, and somehow we got to talking about my savings. I told him how much I had saved up—I think it was about $1,000 by then—thinking he would admire my money management skills. Boy, was I wrong! This was his infamous response: “Are you a f***ing idiot? To save that money?” It was like a slap across my face. He went on. “You came here to make millions,” he said. “Your earning power is going to happen! Do you think you’ll only make 18 thousand a year for the rest of your life?”

Bill Perkins

When I was in my early twenties, my roommate at the time, Jason Ruffo, decided to take about three months off from work to go on a backpacking trip to Europe. This is the same friend with whom I was splitting the rent on a pizza-oven-size apartment in Manhattan: We were both screen clerks making about $18,000 a year. To make a trip like that a reality, Jason would have to put his job on hold—and he’d have to borrow about ten grand from the only person who would lend him that much money: a loan shark. You know, the kind of lender who doesn’t ask for collateral and doesn’t care about your credit report because he has other ways to make sure you pay up.

I said to Jason, “Are you crazy? Borrowing money from a loan shark? You’ll get your legs broken!” I wasn’t worried only about Jason’s physical safety. Going off to Europe meant that Jason would also miss out on opportunities for advancement in his job. To me, the idea of doing something like that was as foreign as going to the moon. No way was I going to go with him. But Jason was determined, so off he flew to London, both nervous and excited about traveling alone with a Eurail pass and no set schedule.

When he came back a few months later, there was no discernible difference between his income and mine—but the pictures and stories of his experiences showed that he was infinitely richer for having gone…

His stories of the interesting cultures he’d seen and the connections he had made were so amazing, I felt pretty envious—and regretful that I hadn’t gone. As time passed, that feeling of regret only grew. When I finally went to Europe, at age 30, it was too late: I was already a tad too old and too bougie to stay in youth hostels and hang out with a bunch of 24-year-olds. Plus, by the time I was 30, I had many more responsibilities than I’d had in my early twenties, which made it that much harder to take months off for travel. I finally, unfortunately, had to conclude that I should have just gone earlier.

Bill Perkins

I’ve written God-knows how many blog posts around the general idea of opportunity costs and why it’s important to invest in experiences early and often, but today, I want to take this idea a step further.

Yes, you should invest in experiences, but as Perkins showed above, investing in experiences doesn’t have to come at the expense of your career. Look at the boss’s reply as well as Bill’s observation when Jason returned:

“You came here to make millions. Your earning power is going to happen! Do you think you’ll only make 18 thousand a year for the rest of your life?”

“When he (Jason) came back a few months later, there was no discernible difference between his income and mine—but the pictures and stories of his experiences showed that he was infinitely richer for having gone…”

So what are the takeaways here?

If you are confident that your earning power will grow exponentially over time, saving every single penny in your early years is a fool’s errand.

If you are a competent, hard-working individual, taking a brief hiatus to explore a side quest or two won’t derail your career.

The truth is, if you’re actually a high performer, and if you’re confident that you will excel in your career, you don’t have to neglect other areas of your life to reach your goals. You’ll reach the same destination, but one journey will be a hell of a lot more fun. It quite literally makes sense to spend some of your early-career earnings on non-work pursuits. Plus, you’ll be a hell of a lot more interesting. Seriously, no one likes the boner at a cocktail party who can’t maintain a conversation without referencing their job or entrepreneurial aspirations at least four times.

So why is this “Grind over everything” mindset so popular? Maybe this is a controversial take, but I think it’s a heavy dose of copium self-administered and propagated by folks who couldn’t achieve success unless they neglected other areas of their lives.

It’s easier to tell yourself that you are better than others because you made sacrifices that they didn’t, rather than admitting that it’s actually quite possible for plenty of people to have it both ways.

Let’s be real, getting rich after spending 10 years doing nothing except “grinding” isn’t impressive. If you fully committed to anything for 10 years and the end result was anything short of a home run, that would be an abject failure. “Success,” financially speaking, should be the default outcome.

You know what’s actually impressive? Learning a musical instrument, fostering deep relationships, traveling somewhere new, picking up a new language, mastering a martial art, and/or developing a decent sense of humor, all while leading a lucrative career.

Don’t pay attention to the hustle gurus who have made their “riches” their entire identities. They fall on the left tail of the success bell curve. Instead, look at the folks whose net worths are just one of their many successes. Believe it or not, you can win the money game without giving up everything else along the way.

- Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!

Jack's Picks

I enjoyed this Ryan Holiday piece on 31 lessons learned about money.

This Nassim Taleb piece on “How to legally own a person” is a fantastic read as well.