Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

Three weeks ago, I was driving to Aspen for a weekend on the slopes, and I just could not get my rental car’s Bluetooth to connect to my phone. Some technological advancements, such as the advent of the automobile, iPhone, and Bluetooth, have been wonderful. Others, such as the inability to connect new Bluetooth devices while a vehicle is moving, are total regressions. After fumbling with the touchscreen for 10 minutes, I accepted defeat and switched to one of SiriusXM’s country radio stations.

After a few hits by Eric Church and Morgan Wallen, the radio host took over the airwaves to discuss whatever it is that radio hosts discuss, which, in this case, included an article about “bucket lists” that she had read the night before. To quote the host:

“We all have bucket lists that state the things we want to do before we, you know, kick the bucket. According to the survey in this article that I read, 60% of people say the biggest obstacle to checking off their bucket list is that they don’t have enough money. Amen to that, I need some more money too.”

The host’s remarks confirmed a thought that I’ve had for a while: most of us have things that we want to do and a life we want to live, and most of us believe that the only thing preventing us from making those desires our reality is a lack of money.

But this idea is a lie.

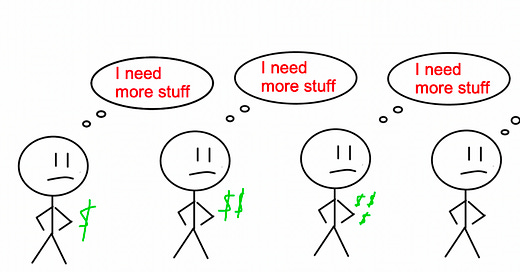

In 2018, Harvard Professor Michael Norton asked 2,129 millionaires how happy they were on a scale from 1-10, and how much money they would need to get to a 10. All the way up the income-wealth spectrum, pretty much everyone said they would need 2-3x as much to be perfectly happy.

Maybe if rich people were perfectly content and doing everything they wanted while poor people needed money to fulfill their dreams, then, yeah, insufficient funds would be the culprit. But the poor, the rich, and everyone in the middle all feel like they just need a little bit more.

I have some thoughts on this.

When you’re poor, your desire for more money comes from a place of scarcity. It’s an existential issue. Credit card debt is real. Emergency medical procedures are real. Automobile repairs are real. When you’re living paycheck to paycheck, you’re one ill-timed catastrophe away from financial ruin. No wonder you can’t get around to your bucket list. Bucket lists are for rich people, and you’re just trying to survive. It’s a hard cycle to break free from because any mishap will send you back to ground zero.

But say you do escape the cycle of poverty. Or, even better, say you never experienced it in the first place. You were born wealthy. Money was never an issue. You went to a good school, you graduated debt-free, you got a good job, and you are in a position to do whatever you want. What do you do now?

Whatever pays you the most money, of course. Why? Because money reflects status. When you’re poor, your desire for more money stems from a need to survive. When you’re wealthy, your desire for more money stems from a need for status, because you are surrounded by other status seekers.

Money is tricky because it’s a scoreboard visible to the outside world. No one knows if your home life sucks or whether or not you are miserable at work, but they can see your job title on Linkedin and estimate how much you make. They can estimate your “wealth” from your apartment, your house, your car, and your watch. And you can estimate the wealth of those around you, too.

You begin comparing yourself to others with money, and you pursue those things that will provide you with the most status and the most money. No one wants to lose the comparison game.

You need to make more money than those around you, or, at the very least, you need to keep up. Anything to avoid the perception of falling behind. Of course, you tell yourself that if you just earn a little bit more you’ll be able to step away from the game. You’ll finally do what you want. But that’s not how this works. Once you grow accustomed to a high-dollar lifestyle, you can’t afford to step away. Stepping away means falling behind. You get stuck on the treadmill.

In the absence of strong convictions about what you want from life, you will always default to wanting more money. It’s the lowest common denominator of desire in a society with any semblance of upward mobility. The key to escaping this cycle is first establishing your priorities (family dynamics, geography, lifestyle, whatever), and then figuring out how to get there financially. Our problem is that we tend to let income determine desire.

- JackI appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!

Jack's Picks

My friend (and CEO/fearless leader of my email platform, beehiiv) Tyler Denk recently launched his newsletter, Big Desk Energy, where he has been giving the inside scoop on his lessons learned building a startup. Sign up here to check it out.

If you’re looking for a new banking solution in 2024, check out my bank of choice, Mercury. My Mercury account has been a game-changer for managing my business expenses, helping me keep my personal and professional money separate. Get started with Mercury here.

Paul Skallas (better known as the Lindy Man on Twitter) published an interesting read on the absurdity of modern day “health influencers.”

I enjoyed this piece by Rob Henderson on the various life stages that men go through, including the “Age 30 Crisis.”

Paul Graham’s latest essay on what makes for “the best essay” is just excellent.