Everything You Can't Predict.

Trends are easy. The winners of those trends? Not so much.

Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

You would be hard-pressed to find a technological development from the last 20 years that is more important than “the cloud.”

I snap pictures on my iPhone, and they are immediately shareable with any of my contacts through the cloud. I collaborate with co-workers in real-time through Google Docs and Google Sheets thanks to the cloud. Massive enterprises like Airbnb use Amazon Web Solutions (the biggest provider of the cloud) to streamline the search experience for their users.

Given its widespread usage, it’s not surprising that the cloud has been quite lucrative for cloud providers.

Amazon, the biggest player in the space, made $80B in revenue and $23B in operating profit from its AWS division in 2022, up from $62B and $18.5B the year before. You can probably guess which companies are the second and third biggest cloud providers too: Microsoft and Google.

Interestingly, the first company to launch an enterprise cloud solution wasn’t Amazon, Microsoft, or Google.

It was IBM.

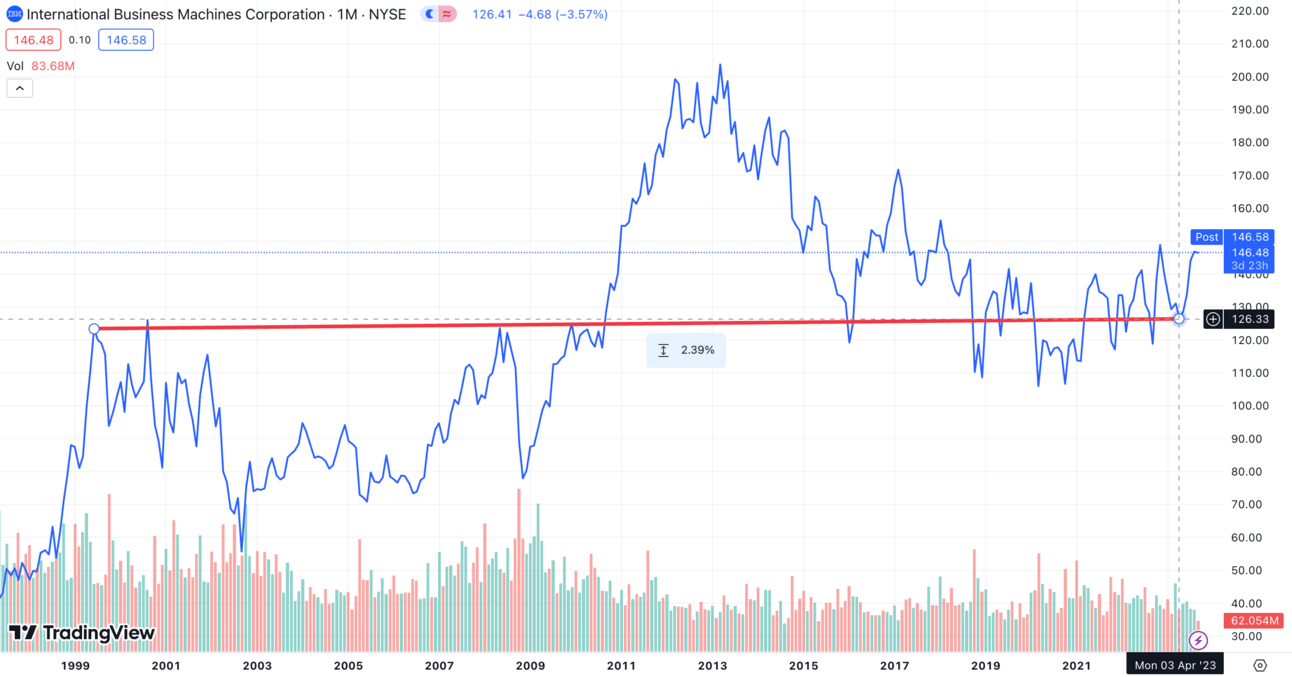

Yes, IBM, whose stock price appreciated by a whopping 2.39% between August 2000 and April 2023, was the first entrant to the cloud space.

So, what went wrong?

IBM was the face of the computer industry for most of the 20th century, and in July 2002, they unveiled a service called Linux Virtual Services, which offered customers a radical new payment structure.

Historically, IBM had locked customers into long-term, fixed-price contracts in exchange for access to different hardware and software products. In contrast, Linux Virtual Services would allow customers to run their own software applications through IBM mainframes and pay based on their usage.

According to IBM, this usage-based payment model would result in savings of 20% - 55%.

Linux Virtual Services should have kickstarted a proliferation of cloud-based services, but instead, it was shut down a few years later. (More on this in a moment.)

Two years before IBM launched Linux Virtual Services, an online marketplace called “Amazon” launched an e-commerce service, Merchant.com, to help third-party retailers like Target build online shopping sites on top of the Amazon e-commerce engine.

As the Merchant.com project developed, Amazon’s engineers encountered a problem: as a startup that was founded just six years earlier, Amazon’s internal infrastructure was a jumbled mess of updates built upon updates. The engineers realized that it would be impossible to build a centralized development platform for 3rd-party use out of Amazon’s current state, so they started from scratch and rebuilt their internal infrastructure with a set of well-documented APIs.

Around this time, then-exec (and current CEO) Andy Jassy also realized that Amazon’s engineers were spending too much time on redundant work. Different teams were all building their databases from scratch when they could have instead shipped applications faster by building on top of databases created by other teams.

Jassy called for a shared IT platform that all engineering teams could access, and this change yielded an immediate productivity boost for Amazon’s engineers.

Noting their internal success, Amazon opened its platform to all developers in July 2002 (around the same time that IBM launched its Linux Virtual Services), and by 2004 hundreds of applications had been built on Amazon’s platform.

As more and more developers gravitated to their platform, Andy Jassy realized there was an opportunity to build what he called an “Internet Operating System,” with Amazon at the center of the ecosystem.

Jassy identified databases, storage, and compute power as infrastructure pieces that Amazon could sell as services, and in 2006, around the time that IBM shut down its Linux Virtual Services, AWS officially launched its first cloud storage solution.

We all know what happens next:

In 2002, IBM, a $130B computing giant with unlimited resources and a multi-decade head start, launched an enterprise cloud offering aimed at commoditizing computing power.

In 2002, Amazon, a $10B e-commerce store, was solving an internal engineering bottleneck.

In 2006, IBM shut down its cloud storage service.

In 2006, Amazon launched its cloud storage service.

In 2023, IBM is still worth $130B.

In 2023, Amazon is worth 10 IBMs, largely due to the success of AWS.

What went wrong at IBM? No one really knows, but Corry Wang, a former equity researcher at Bernstein, speculates that IBM’s sales team may have had misaligned incentives. In 2002, sales teams would have earned larger commissions on higher-priced, fixed contracts than on cheaper, usage-based contracts, and the new offerings would have cannibalized current customers as well. Why, as a salesperson, would you sell a service that made you less money?

Meanwhile, Amazon realized, almost by accident, that their internal solutions to infrastructure bottlenecks could be exported and sold as services. And Amazon didn’t have current SaaS customers to worry about cannibalizing, so their salespeople were free to sell the service to anyone.

16 years later, Amazon is the market leader in cloud, and IBM is stuck in 2006.

So why tell you this story?

Because it shows that predicting the future is easy, but predicting who wins in that future is much, much more difficult. By 2001, plenty of tech experts could have told you that cloud computing was going to emerge as an important technological development in a decade.

But how many of those experts would have predicted that an online bookstore would dominate the cloud market?

Picking trends is easy. Picking winners is hard.

I think artificial intelligence will fundamentally change how we engage with our work by 2033. Most of you would probably agree with that take. The real question is which companies will dominate the next decade because of AI?

The biggest AI company of 2033 may be an AI startup today, or it may be a large company that has yet to be associated with AI, or it may not exist at all.

The range of possible outcomes is wider than you could possibly imagine.

You might not think of Spotify as an “AI” company, but they are now leveraging AI to translate podcasts into different languages. What if they further leverage AI to play different targeted advertisements for different listeners, all in the hosts’ voices? Overnight, a music streaming platform could become a dominant AI platform.

Nobody would have expected that just two years ago.

Do you really think the equity analyst covering Amazon in 2002 was including the hypothetical value of a non-existent cloud storage division when calculating the company’s NPV in 2002? Absolutely not. Amazon sold books, DVDs, electronics, and home goods. And yet, 20 years later, that cloud storage division is responsible for 2/3 of a trillion-dollar company’s operating income.

Trends are easy. Specifics are hard.

- Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!

Jack's Picks

For years, The Investor’s Podcast Network has been one of the best sources in market news, and they now provide daily commentary and expert insights in the We Study Markets newsletter. Learn the three biggest stories in financial markets each day, explained simply, by signing up for free.

Matthew Ball wrote a wild piece on big bets made by big tech that covered how much Google pays Apple to remain the default search engine on iPhones.

I was featured in this Insider piece covering why Linkedin is so weird.

Just revisited Paul Graham’s 2014 essay on "How to be an expert in changing the world.” Excellent piece.