Infinite Games

There's more to the game than winning it, you know.

Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

The outcome of a finite game is the past waiting to happen. Whoever plays toward a certain outcome desires a particular past. By competing for a future prize, finite players compete for a prized past.

James Carse, Finite and Infinite Games

In October 2020, I was walking toward a squat rack in my local LA Fitness when I saw an old friend across the gym. We made eye contact, recognized each other, and I walked over to say what’s up.

“Joe Stark, it’s been a minute!”

“Raines? What’s up man! I didn’t know you lived in Atlanta now.”

Joe and I had met in high school while playing basketball for rival schools, and we hung out frequently in college when I visited Athens, as he was fraternity brothers with several of my friends.

We realized that we worked out at the same gym and lived five minutes from each other, so we grabbed dinner later that week to catch up. Joe told me that he was living with five friends in a huge house in Buckhead, and their backyard included a pool, hot tub, and half-court.

It was a 23-year-old dude’s dream residence.

“We have a group of 20 guys who play 3-on-3 a few times per week, you should come on Monday!” he told me.

If you have ever played basketball in an LA Fitness, you know just how bad that experience can be. The gym is full of washed-up 29-year-olds who think they are headed to the G-League any day now, despite their inability to shoot, pass, or defend. Every game is a 1 v 5 dribbling exhibition with the occasional 25-foot contested jump shot, and every foul call, no matter how justified, leads to a 10-minute argument punctuated by a veiled invitation to “take this outside.”

So yeah, I was thrilled to have an alternative hoop venue.

For the next six months, I spent 2-3 afternoons per week at the “Old Ivy House” playing 3 v 3 basketball with this new crew.

Every day we would play games to 15, and the winners would stay on the court while the losers would sit out until it was their turn to play again. Then the sun would set, we would head home, and we would come back the next day.

Who was the best player on the court? I have no idea. It depended on the day, really.

Who won the most games over those six months? Who was our “champion?” We didn’t have one. There was no recognition, no title, no nothing.

So why did we play?

Because we enjoyed the game. In fact, the only reason that we kept score was to decide who would continue playing the game. The game was the prize.

In the opening chapter of Finite and Infinite Games, author James Carse states, “There are at least two kinds of games: finite and infinite. A finite game is played for the purpose of winning, an infinite game for the purpose of continuing the play.”

In Spring 2021, basketball at the Old Ivy House was an infinite game. We played for the purpose of continuing to play.

In contrast, high school basketball was very much a finite game. Of course, the game was fun, but the goal wasn’t “to have fun.” The goal was to win championships: first regional, then state. Most organized sports, from high school, to college, to professional, are finite games. Anyone who has played a sport knows this: no matter how much fun you had playing, the goal was always championship or bust.

You could have a phenomenal season, but if it ended with a second-place finish, it felt empty. Incomplete. It was a finite game, and you failed to finish the job.

This idea of finite and infinite games doesn’t just apply to sports such as basketball. In fact, it is much more applicable to the biggest game of them all: life.

We humans have created quite the scoring system, haven’t we?

Are you single? Married? Do you have kids? What do you do for a living? Who do you work for? How much money do you make? Where do you live? How many languages do you speak?

We ask, “Who are you?” but we mean, “Which boxes have you checked?”

And the definition of you, whoever “you” are, is the sum of your boxes. Of course, we don’t consciously analyze our lives in this way. That would seem so vain! But we do it all the same.

Let me give you an example.

What is “prestige?” Well, that’s a broad question. Let’s get more specific. What makes “prestigious” careers prestigious?

You might say exclusivity. Thousands of individuals apply for a limited number of positions, and the ones who successfully land those limited positions become part of the “in-group.” And sure, exclusivity plays a role. But prestige runs deeper than exclusivity alone: prestige represents victory.

You had to beat countless other applicants to land that competitive position. You won, they lost, and your prize includes the prestige that ensues. I’ve won some prestige games myself over the years, like getting accepted to Columbia Business School, for example.

Prestige is a finite game. You play the prestige game for the sake of winning it. But do you know what happens after you win this game? Sure, there’s a moment of dopamine-induced satisfaction as you climb the proverbial mountain, look across the horizon, and scream, “I DID IT! LOOK AT ME!”

But what happens next?

You return from the peak and think, “Damn. I need that rush again. I need to climb another mountain.” But here’s the thing about that next mountain: it has to be greater than the previous one. If not, you’ll only feel underwhelmed as you look out from its peak and see your taller, greater feat from the past taunting you.

And another finite game begins. James Carse explains it best:

The more we are recognized as winners, the more we know ourselves to be losers. That is why it is rare for the winners of highly coveted and publicized prizes to settle for their titles and retire. Winners, especially celebrated winners, must prove repeatedly they are winners. The script must be played over and over again. Titles must be defended by new contests. No one is ever wealthy enough, honored enough, applauded enough. On the contrary, the visibility of our victories only tightens the grip of the failures in our invisible past.

James Carse, Finite and Infinite Games

Here’s the problem with treating life as a series of finite games that must be won: No one remains the winner forever.

This is true at the world’s biggest stages. If you win the Super Bowl, you have just one week to celebrate before the offseason begins once more, and you’re once again one of thirty-two teams fighting for next year’s throne. New season, the same finite game. And in this pursuit of finite games, life becomes a continuous challenge, an incessant chain of competition after competition with no respite.

We see this in our careers all the time. Every goal is merely another step to reach another loftier goal. To quote myself from October:

Get good grades in high school to get into a good college to get a good job with a good salary to get promoted to a better job with a better salary. Maybe we go to graduate school or attend different training programs to make us more attractive employees.

The game continues as we climb the corporate ladder. More money. More prestige. More responsibility. This game doesn't have time for your "dreams". When you are playing the game, the logic behind every single decision we make is simple: Will this help me advance in this game?

It’s corporate Candy Land, and the rules are win or bust. But when the only purpose of the game is to win the game, it devalues the game itself.

There is a contradiction here: If the prize for winning finite play is life, then the players are not properly alive. They are competing for life. Life, then, is not play, but the outcome of play. Finite players play to live; they do not live their playing. Life is therefore deserved, bestowed, possessed, won. It is not lived.

James Carse, Finite and Infinite Games

Taken to its furthest extreme, the focus on outcome over everything leads to us discounting 99% of our lives for the sake of a few, small, fleeting moments that might provide some sense of satisfaction before the cycle begins anew.

And, I don’t know man, it seems pretty insane to live your life this way, but we do it all the time. You see it among the most successful folks alive, who, despite their billions of dollars and fame and fortune can’t stop chasing that next mountain. That next achievement. Because the last one, which took years to accomplish, lost its luster in minutes.

You see it in the disciples of the FIRE movement, who cut every expense and invest every dollar to escape the rat race as quickly as possible, only to exit the labor market, look around, and wonder, “Well, now what?”

The most dangerous story that’s ever been told is happiness lies just beyond achievement. And you can spend your whole life following that story just to find that there really wasn’t a pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

Sorry to spoil the party.

“SO WHAT JACK? WE SHOULD JUST EXIT THE LATE-STAGE CAPITALISTIC MACHINE AND LIVE OFF THE LAND IN SOME SORT OF NOMADIC EXISTENCE THAT REJECTS 21ST-CENTURY MATERIALISM? BECAUSE THAT SEEMS LIKE THE LOGICAL CONCLUSION TO THIS WHOLE THING.”

Well, no. That would be a pretty lame way to live as well, tbh.

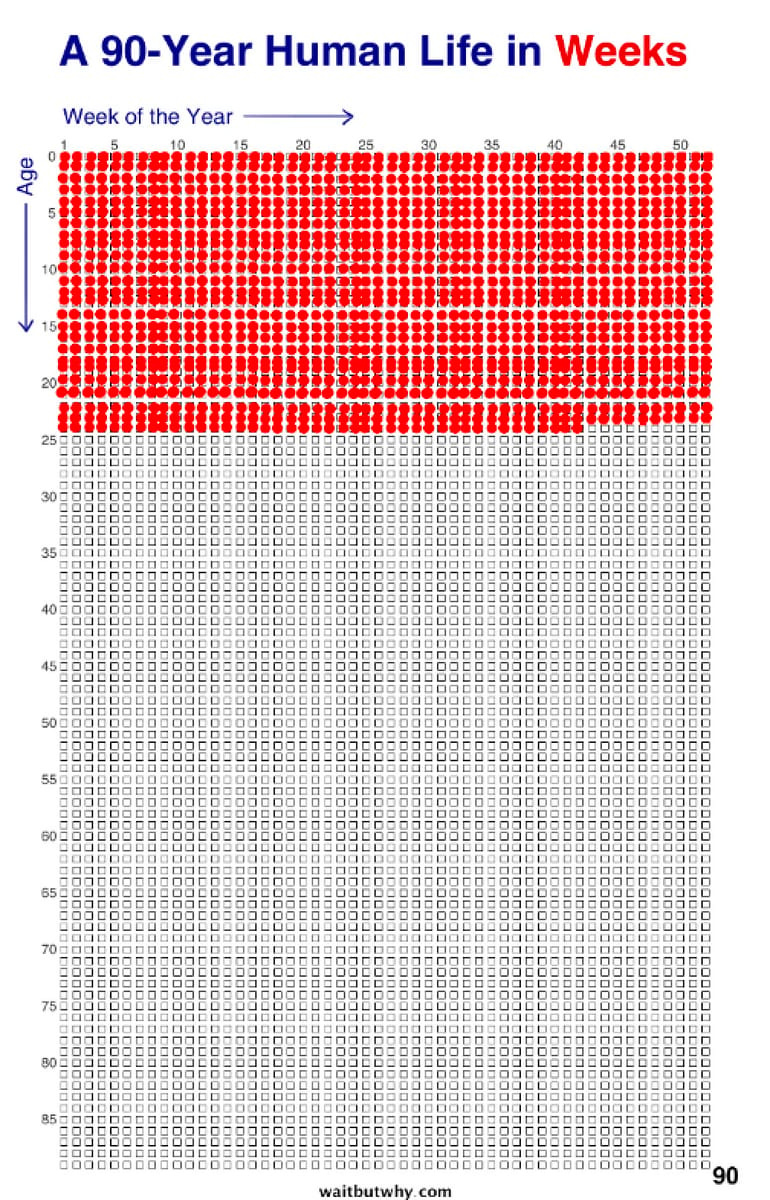

My message isn’t that you should reject and abhor success and achievements. It’s that you shouldn’t spend your estimated 4,680 weeks in hot pursuit of some singular accomplishment that likely won’t satisfy you for even one of those 4,680 weeks.

You should instead spend your 4,680 weeks in pursuit of the things that you actually enjoy pursuing. Accomplishments should be the byproduct of your pursuits, not your only motivation. Yes, let achievements mark milestones in your life, but don’t let achievements define your life.

If you’re not having some fun along the way, then what’s the point? To close out with one more quote from Carse:

An infinite player does not begin working for the purpose of filling up a period of time with work, but for the purpose of filling work with time... Work is not a way of arriving at a desired present and securing it against an unpredictable future, but of moving toward a future which itself has a future.

James Carse, Finite and Infinite Games

The finite and infinite player can accomplish the same things, but doing the work for the sake of doing the work will certainly make the journey more enjoyable, won’t it?

- Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!

Jack's Picks

“Depression and anxiety are considered “disorders” and the most common remedy is pharmaceutical medication. The goal here is to trick a person’s biology into feeling OK about their life and the world they live in, even if their life and world doesn’t change.” Jonathan Carson wrote a really interesting piece on reframing anxiety and depression.

Wonderful read! I think you only realize this after summiting the wrong mountain and realizing that the happiness doesn't last. This reminds me of a podcast episode on Modern Wisdom with Ryan Holiday: https://open.spotify.com/episode/4Z1jubMx7SqAUohGCx0vaj?si=7d26261748d04e77

Come over to my substack and read it until Jack comes back from writing his book: https://gainswithvranes.substack.com