Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

The “Dot Com” bubble is a well-known chapter in the history book of financial markets. As internet usage exploded in the 90s, the idea of “reasonable” valuations flew out the window. Tech startups with nothing more than trendy domain names could raise millions of dollars by showing investors that they were attracting millions of clicks (which isn’t a GAAP-recognized metric, by the way), and this mania hit its peak when the now-infamous Pets.com reached a ~$400M market capitalization.

I don’t have to rehash the collapse of this “Dot Com” bubble, but you know what happens next: funding dried up, these previously high-flying companies failed to turn a profit, and most of them went bust.

But one company didn’t go bust: Amazon.

Despite its stock price collapsing by >90% from its peak, Amazon managed to survive the tech apocalypse of the early 2000s and grow into a $1.4T company.

Not bad for an online bookstore.

But it shouldn’t be a surprise that Amazon survived. Amazon was founded by Jeff Bezos, one of the brightest entrepreneurs of our generation. Surely, Bezos’s savvy leadership separated Amazon from the hundreds of other internet startups that didn’t survive the crash, and his instincts helped him navigate one of the most turbulent markets in history, right?

Not exactly.

The truth is that while Bezos was probably a fantastic CEO, his company’s survival came down to a timely bond sale just before the market collapsed.

In Brad Stone’s bestseller The Everything Store, the author explains how a well-timed debt deal likely saved Amazon from suffering the fate of its Dot Com peers:

Early in 2000, Warren Jenson, the fiscally conservative new chief financial officer from Delta and, before that, the NBC division of General Electric, decided that the company needed a stronger cash position as a hedge against the possibility that nervous suppliers might ask to be paid more quickly for the products amazon sold.

Ruth Porat, co-head of Morgan Stanley’s global-technology group, advised him to tap into the European market, and so in February, Amazon sold $672 million in convertible bonds to overseas investors. This time, with the stock market fluctuating and the global economy tipping into recession, the process wasn’t as easy as the previous fund-raising had been. Amazon was forced to offer a far more generous 6.9 percent interest rate and flexible conversion terms — another sign that times were changing. The deal was completed just a month before the crash of the stock market, after which it became exceedingly difficult for any company to raise money. Without that cushion, Amazon would almost certainly have faced the prospect of insolvency over the next year.

Without Warren Jenson, no one knows who Jeff Bezos is today.

That $672M convertible bond sale separated Amazon from the hundreds of other internet startups that didn’t survive the crash because it increased Amazon’s margin of safety.

According to Investopedia, “margin of safety” is a principle of investing in which an investor only purchases securities when their market price is significantly below their intrinsic value.

In layman’s terms, a margin of safety is an estimate of how “wrong” you can be and still be okay.

Margins of safety aren’t discussed much because they’re boring, like life insurance. We prefer this romanticized idea of the swashbuckling entrepreneur who throws caution to the wind to chase their dreams, overcoming trials and tribulations on their way to success.

But that idea just doesn’t match reality.

The companies and entrepreneurs that succeeded weren’t necessarily the best. Oftentimes, they were just the ones that survived.

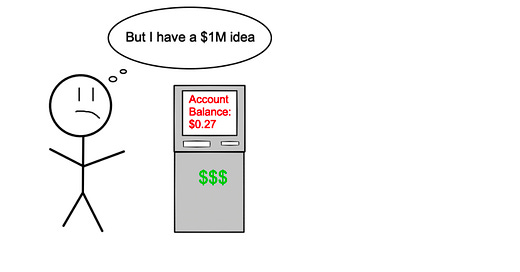

Your odds of success have more to do with the length of time that you can “afford” to fail than the quality of your ideas or execution, because the swashbuckling entrepreneur can only throw caution to the wind until he loses his ability to pay the next month’s rent.

Don’t believe me? Even one of the greatest entrepreneurs of our time, Elon Musk, admits that SpaceX would have failed without the capital he had gained from his previous ventures: PayPal and Zip2.

SpaceX was a cash incinerator for years, but Musk’s gains from his previous ventures provided a margin of safety by giving him enough time to figure the business model out.

Margins of safety aren’t sexy. Crazy, daring ideas are. But crazy, daring ideas take money and time to be realized, and without adequate capital, those ideas rarely survive.

For startups, a large funding round could provide a multi-year runway to reach profitability. Much like in 1999, the startups that raised massive rounds in 2020 and 2021 and showed some discipline in their spending habits bought themselves time to turn profitable.

For solo entrepreneurs, a large savings account, a massive liquidity event, or a job that pays a good salary while giving you the freedom to build your own business all provide a large margin of safety.

Whether you’re building a company or striking out on your own, it’s a good idea to think about how wrong you can be and still have everything work out in your favor.

- Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!