Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

Can't Stop, Won't Stop, GameStop

In the fall of 2020, GameStop was a left-for-dead video game retailer. A world dominated by eCommerce and software had no place for a brick-and-mortar relic from an earlier time. Everything changed when Ryan Cohen, the founder of eCommerce dog food company Chewy, took an outsized stake in GameStop.

Suddenly, the left-for-dead retailer showed signs of life. Given Cohen's pedigree, rumors of an eCommerce pivot began circulating.

While Cohen was buying $GME stock hand over fist, professional investors were busy shorting it to $0. Eager to pile on the dying video game retailer, hedge funds collectively shorted more than 100% of GME's outstanding shares.

In late 2020, an older Reddit post from September 2020 detailing how GameStop could become the "greatest short burn of the century" was rediscovered.

By January 2021, this short squeeze thesis had spread like wildfire across Twitter and Reddit. A 'David and Goliath' narrative emerged, where GameStop's stock price was a power struggle between millions of retail investors and greedy hedge funds. Retail buying could push the price up to a point that some hedge funds would have to 'buy to close' their short positions.

This buying would incite more buying, which would squeeze more hedge funds to close their positions, and the cycle would accelerate. With enough buying pressure, GameStop's stock could jump more than 1000%.

Sure enough, it happened.

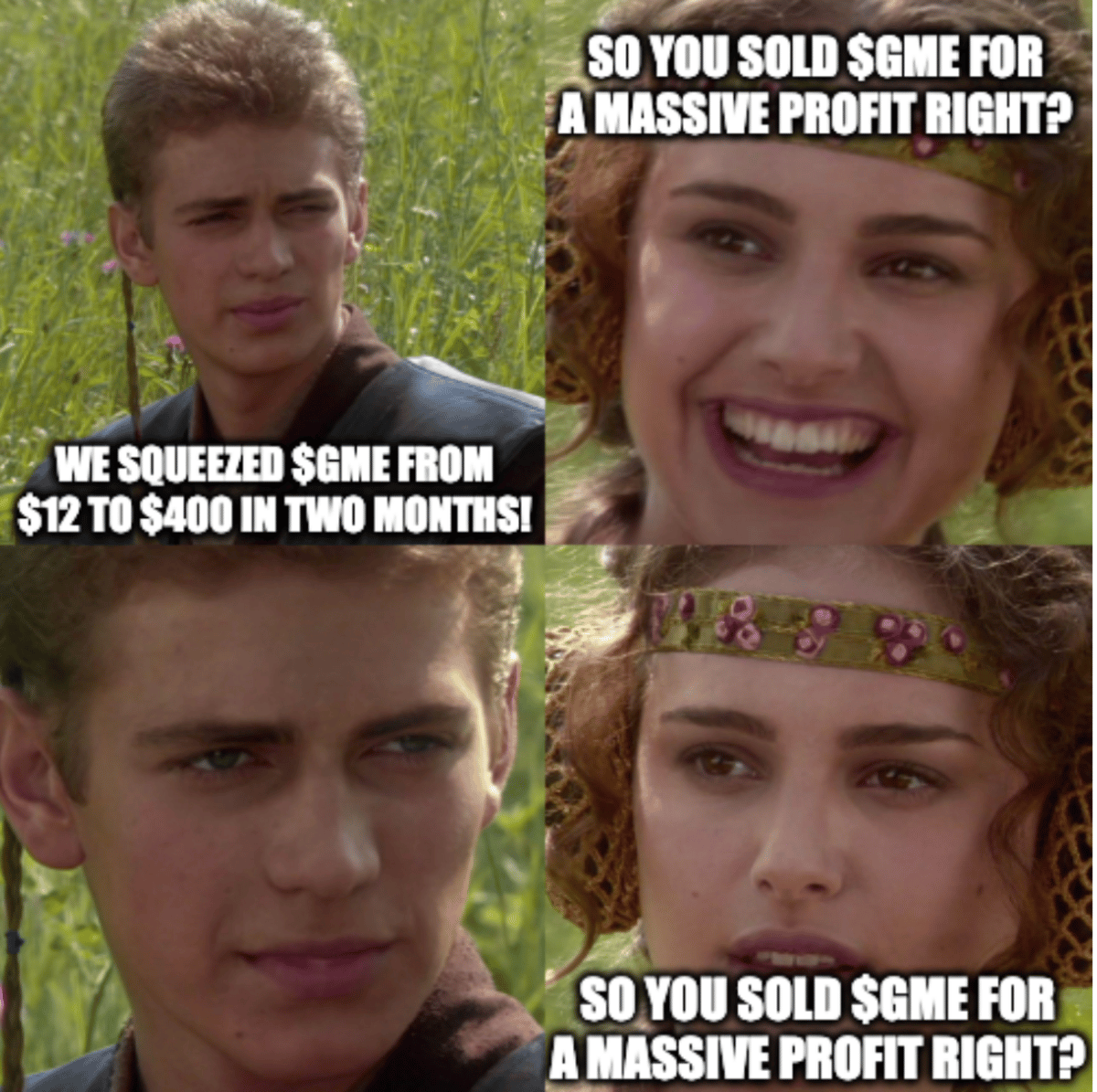

Between November 2020 and January 2021, GME's stock price exploded from $12 per share to more than $400. At its peak, GameStop was worth an astounding $22B.

Retail investors won. Several hedge funds suffered catastrophic losses, most notably Melvin Capital, which experienced a 53% drawdown in January 2021. Retail investors must have closed their positions to book million-dollar profits, right?

lol, lmao.

3000% gains in two months weren't good enough, I suppose. Calls to "HODL" and "keep buying" flooded the web, and the line between investment thesis and cheerleading blurred. What began as an investment thesis catalyzed by a short squeeze evolved into identity politics.

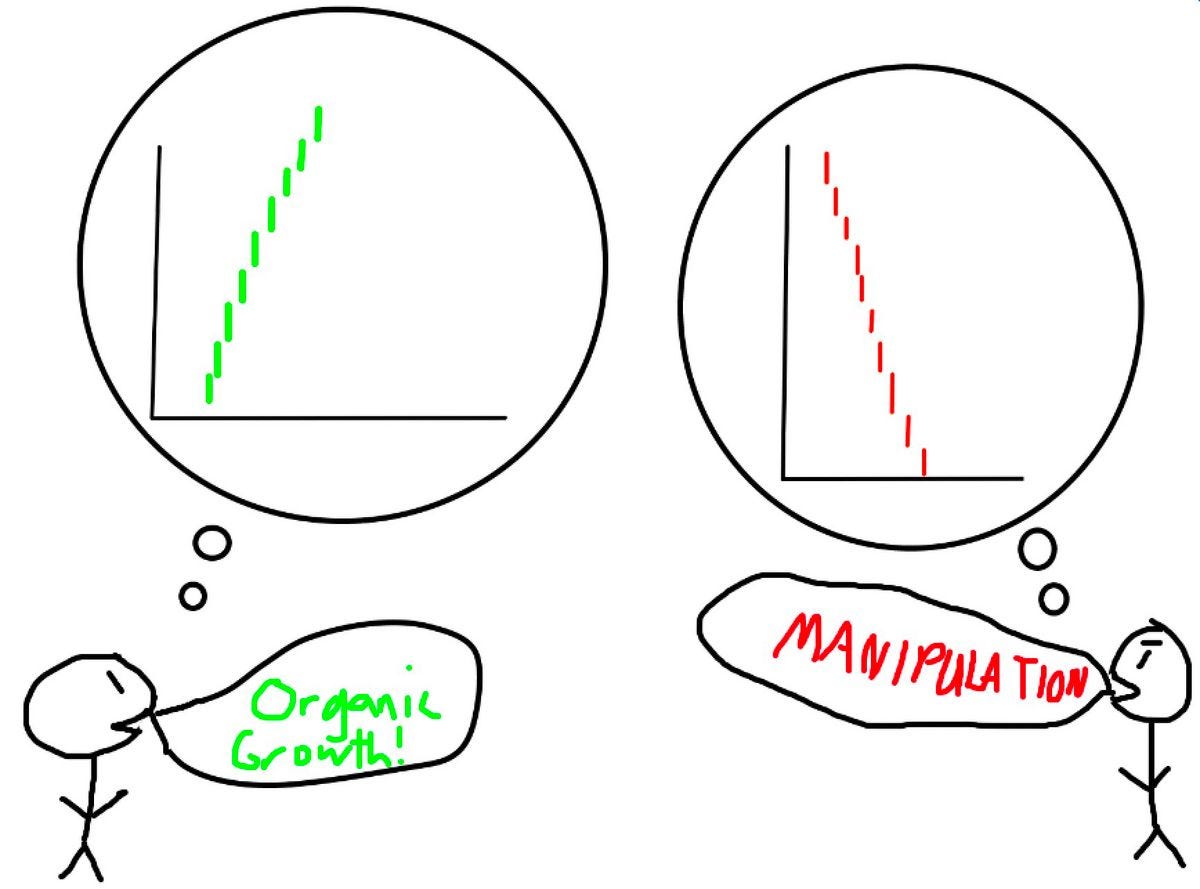

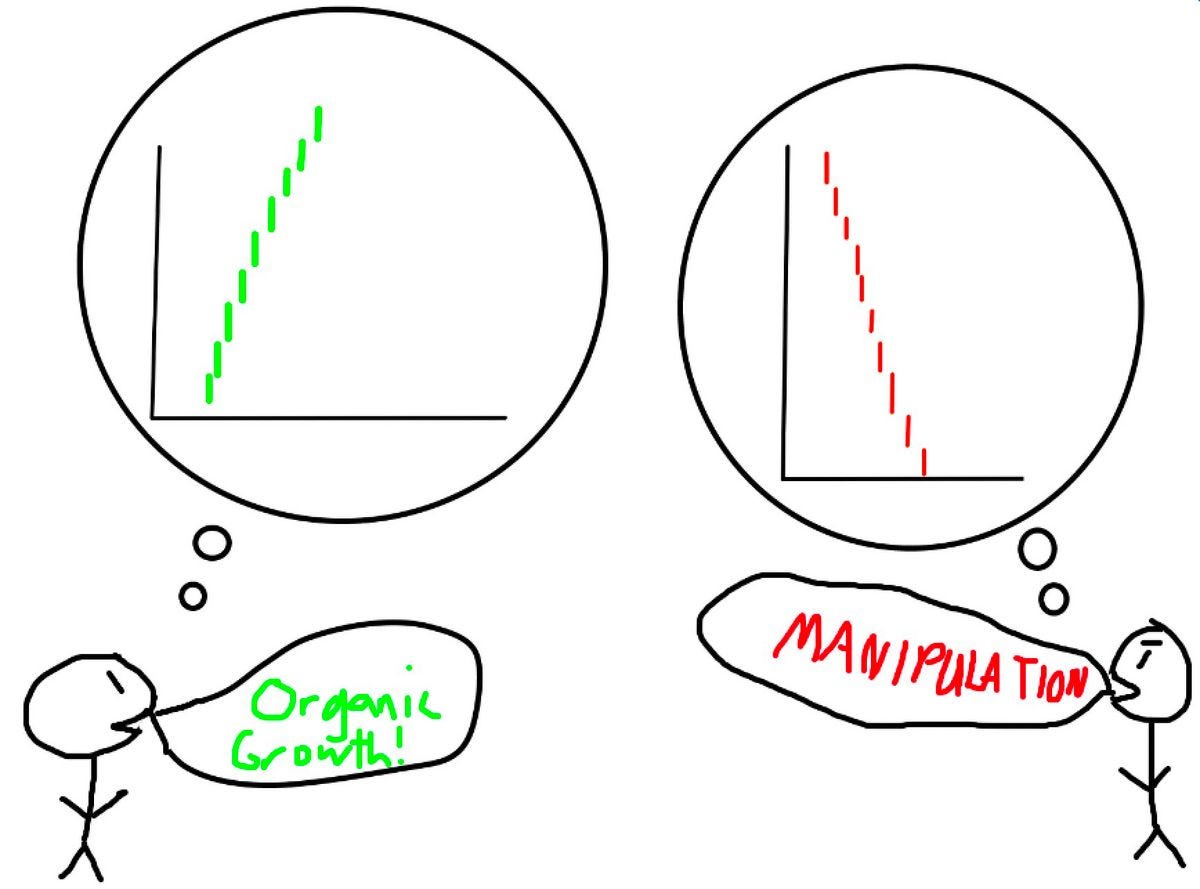

Any negative price movement was dismissed as market manipulation. HODLers refused to sell their precious $GME shares, because the fair value was obviously $2500 a share if you accounted for all sorts of conspiracy theories floating around.

The move from $12 to $400 in a matter of weeks, which was largely fueled by a short-squeeze of epic proportions, was obviously organic price discovery. Any subsequent decline in price, back to *checks notes* a price point still more than 10x higher than a few months earlier, was blatant manipulation.

As investors screamed manipulation, the price of $GME continued sliding back down. Today, GameStop is down 70% from peak, sitting at $120.

Note that this is still 10x higher than November 2020.

The Psychology of Stocks Going Up

What's going on?

Last week, I discussed different investor fallacies in Being Right for the Wrong Reasons. To quote myself:

Correlation rarely equals causation. However, we are pretty terrible at realizing this, especially when money is involved.

Me

Money has a powerful impact on our psyches. When a stock goes up after we buy it, we assume that it went up because of our investment thesis. In the case of GameStop, countless investors believed the "us vs. them" zeitgeist that they saw on social media, and they FOMO purchased shares as a result.

GameStop's run from $12 to $400 reinforced this idea, further entrenching the belief that $GME shareholders were on the "right team". If you believe that you are on the right team, any decline in stock price has to be manipulation by greedy hedge funds, right?

None of these "investors" ever stopped to think, "Hmmm, perhaps a declining video game retailer that experienced a once-in-a-decade short squeeze isn't worth $22B. The explosion from $12 to $400 was an extraordinary occurrence, and the subsequent decline in price is a return to fair value now that short interest has dropped."

Can't Pay Too Much for Growth

GameStop is a low-hanging fruit. Most investors would tell you the $GME short squeeze was anything but normal. How about a real growth stock?

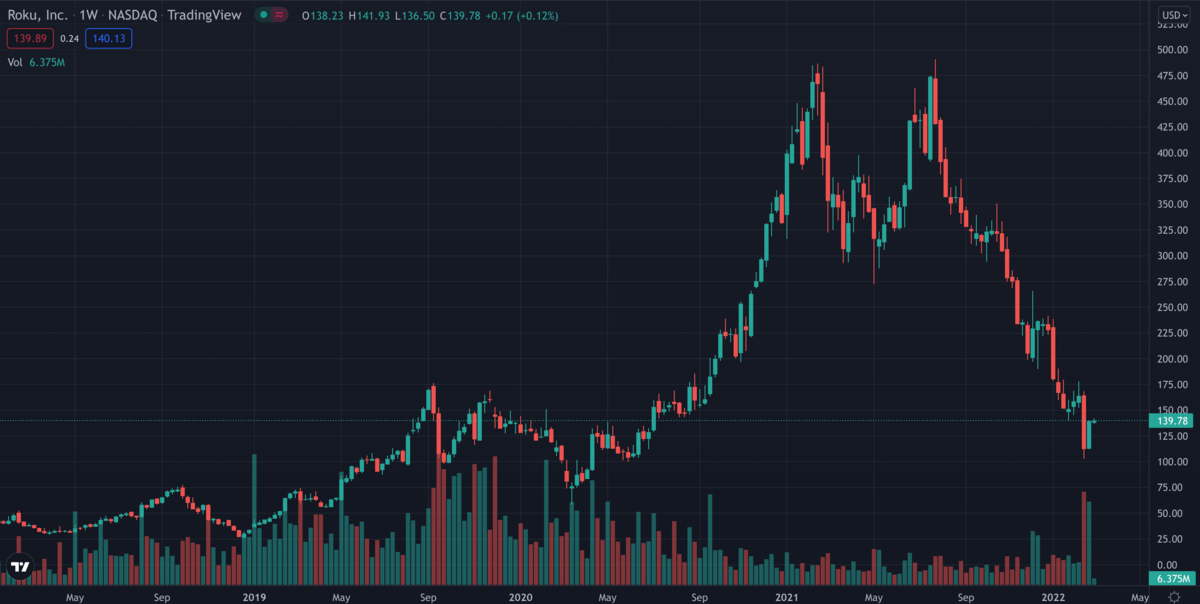

Enter Roku: a profitable streaming platform with 49% yoy revenue growth.

Roku experienced insane price appreciation through 2020 and early 2021. It also experienced a 70%+ drawdown from its peak. This isn't a short squeeze-induced meme stock. This is a company with solid fundamentals, excellent growth prospects and a massive addressable market.

What happened? Long story short, Roku got ahead of its valuation, but many investors didn't sell.

Suppose you bought Roku at $75 in March 2020. You correctly predicted that a streaming platform would perform well during lockdowns, ad spend on Roku wouldn't decline, and fears of losing market share to Amazon were over-exaggerated.

At its peak last June, Roku hit $475, and the streaming platform was worth $60B on a run-rate of ~$2.5B in revenue. Thesis proven correct, and Roku is now expensive. Time to take profits. Except you didn't take profits. Why?

Because at some point on the way up, your thesis for future price appreciation became a justification of current price. You bought Roku because you believed the March 2020 drop was unjustified. Roku recovered to its pre-covid highs. Then $300. Sure, it's a bit expensive. But revenue is growing like crazy and demand is at all all-time high. By the time Roku hits $475, the "undervalued" thesis doesn't exist anymore. However, you believe that the current price is supported.

"Roku is undervalued because of _____" becomes "Roku looks expensive, but the current price still makes sense because of ______".

When Roku was $75, you probably would have planned to sell at $400. But you normalize price movement on the way up because it validates your investment thesis.

You developed your thesis at $75 a share, and price movement confirms that you were right.

$150

$300

$450

Revenue growth is still good and market share is still expanding, so you stay long. In your head, the market bid your stock to $450, so this is now the fair price for Roku.

This line of thinking ignores two points:

The characteristics that made Roku a strong buy at $75 may no longer be relevant at $450

The market may have been wrong, and you just happened to benefit in the short-term

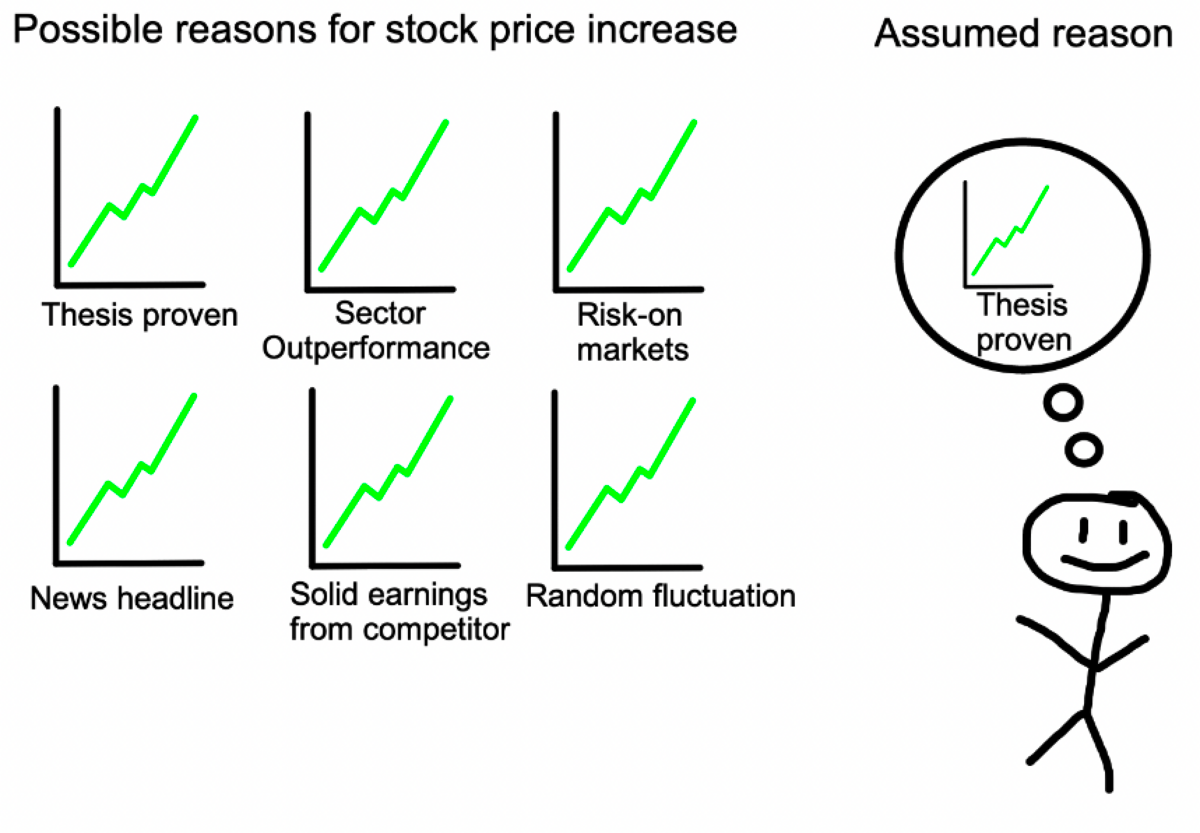

Price temporarily going up doesn't necessarily mean that your thesis was correct. It just means that the market is bidding up your stock. This could happen for a number of reasons.

Evangelical Investing

Exponentially higher price movements should increase the likelihood that investors sell, especially when price appreciation outpaces the gains of underlying fundamentals like revenue or profit growth.

You buy a stock because it's undervalued, and it jumps 1000% while revenue is only up 250%. It isn't undervalued anymore. Sell the stock.

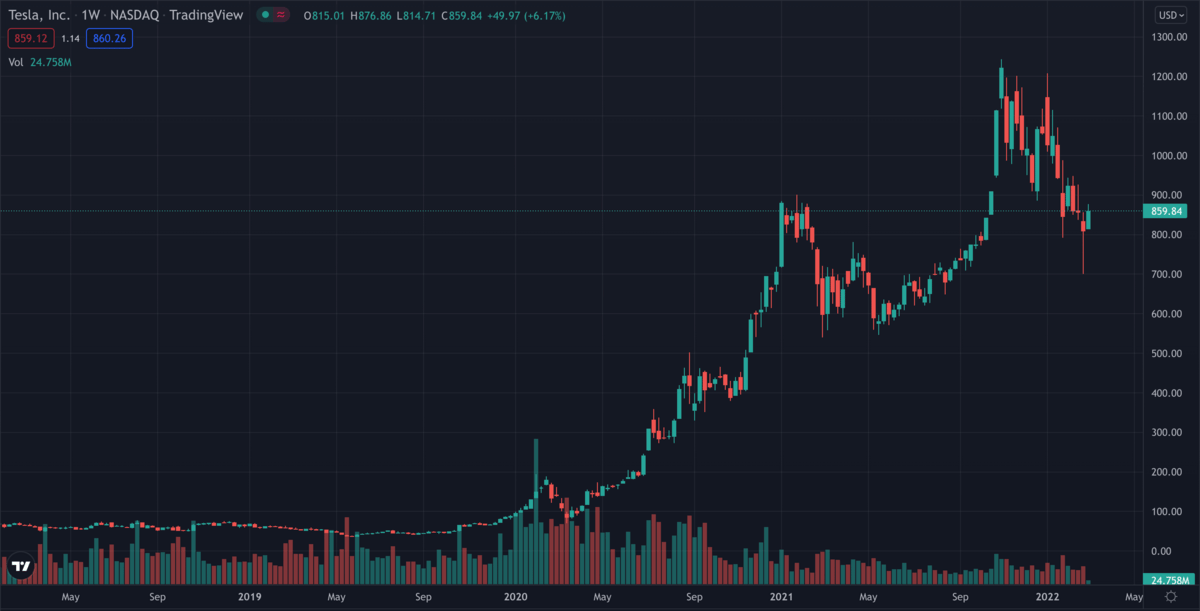

But in reality, the opposite occurs. The biggest price increases create the most fervent believers. Tesla is a great example. If you bought Tesla in 2018 because you (correctly) believed that they would dominate the future EV market, you were paid handsomely.

Tesla's stock price jumped from a split-adjusted $60 per share in Q4 2018 to $1200 in Q4 2021, a ~2000% increase. Meanwhile, Tesla increased revenue from $7.2B to $17.7B, a ~145% increase. With a healthier balance sheet and expanding profit margins, Tesla deserves a higher valuation than in 2018. However, price appreciation massively outpaced revenue growth.

But if you made a fortune on Tesla, Tesla is all you know. You bet big on innovation and hit the jackpot. Why would you invest anywhere else? The price movement on the way up simply validated your thesis, with each 100% gain becoming the new normal price for the stock.

Tesla's outperformance over the last year was the market confirming that you were right, so you decided to go all in on the EV maker. You quit your job and use your Tesla shares as collateral for margin loans.

All is well, as long as the stock doesn't tank. But what if you're wrong?

Redfin Deadfin

Several small and mid-cap growth stocks peaked in February 2021. Redfin, a tech-based real estate company, was one of these stocks. A Twitter user named "Bahama Ben" had taken aggressive positions in a number of mid-cap growth stocks in 2020, and his portfolio performed well as a result.

His Twitter audience grew to 50k+ followers, and he became the most outspoken Redfin bull on the internet. His thesis made sense: the company had strong management, remote work freed workers to relocate, and low interest rates incentivized home buying.

When Redfin began dipping in March, he allocated more and more capital to the stock.

The February 2021 peak became a price anchor for Redfin's fair value to Ben, as the climb from $9 to $90 verified his investment thesis. However, the stock continued dropping, and by May it was down ~ 50% from its February highs. Ben made it 50% of his portfolio.

Now? Redfin has fallen another 60%.

Redfin has more than round-tripped covid, and it's worth less than it was in January 2020. It would take a 400% gain from here to hit its February 2021 peak again, and there is a strong chance that Redfin never gets there.

But the 2020 climb had validated Ben's $RDFN thesis, so the ensuing decline must have been the market mis-valuing the stock. He is now all-in on Redfin.

One stock in this investor's portfolio became a 50% allocation after a 50% drawdown, and a 100% allocation after an 80% decline. Meanwhile, the S&P is up 15% since Redfin peaked.

On the way up, Ben's confidence in Redfin appreciated with the stock price, both peaking in February 2021. However, as the price tanked, conviction remained. He bought every dip until going all-in last week.

This could be a 6-7 figure loss depending on his portfolio size. Maybe Ben is right. Perhaps the market has been wrong over the last year, and Redfin will climb to $100 a share. But what if the market was wrong in 2020, and it overestimated Redfin's ability to compete in the housing market?

What if Ben profited not from the market correctly identifying a shift in real estate trends, but from the market incorrectly overstating a shift instead? What if the gains were irrational, not the losses?

Ben's Twitter activity made it easy to highlight his journey with Redfin, but countless investors fall victim to these biases. It happened to me as well when I was trading SPACs.

When our stocks go up, we grow more confident in our theses, but prices can temporarily increase for any number of reasons that have nothing to do with our investment theses. When we wrongly gain confidence from an irrational increase in price, we dismiss very rational decreases in price. This leads to us holding or increasing our positions when it would actually be more prudent to sell.

The market isn't wrong. It's just the market. The only thing "right" or "wrong" is how we respond to the market. Be wary of assuming that profitable price movement confirms your ideas, and don't dismiss every dip as the market being irrational.

And if you find yourself down 50% while the indexes keep climbing, the market isn't wrong. You probably just bought a bad stock.

- Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!