Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

I traded SPACs pretty heavily in 2020 and 2021. At my peak, I had turned $6,000, a single Roth IRA contribution, into ~$400k. Since I was, in my head, a stock market wizard, I wanted to share my newly-minted market wisdom with the rest of the world.

Naturally I googled, "How do you make money writing about stocks?"

I quickly found my answer: Seeking Alpha pays authors to write premium pieces on their site. The typical pay was a $40-$50 flat price + a variable payment based on clicks.

What a great idea! I could write about stocks that I had already been researching and get paid to publish my thoughts! I was sold, and I started churning out pieces immediately. The research process would go something like this:

Find a stock with a decent fixed rate that I was somewhat familiar with, research it for a couple of hours, and write the piece. I could make $100+ for a few hours' work.

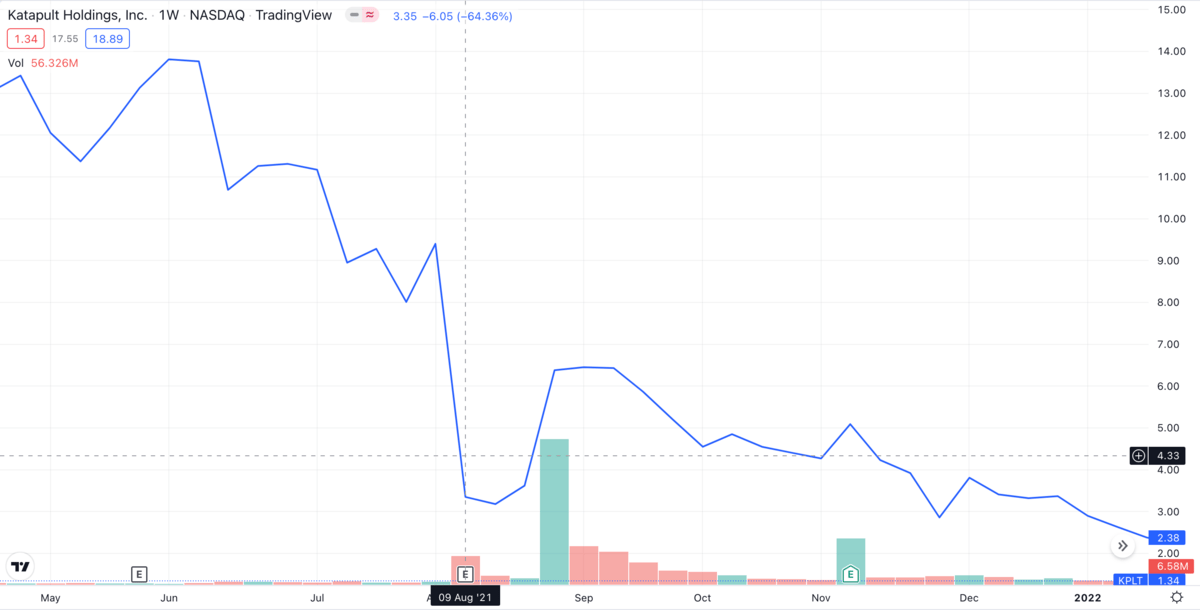

So one day, I found a company called Katapult. Katapult had recently gone public through a reverse merger with a SPAC. This company was a buy-now, pay-later (BNPL) financer, similar to Affirm and Afterpay. Unlike Affirm and Afterpay, Katapult was both profitable and under-covered by the media. Katapult was also growing its revenues by 80% year over year, and it was trading at 1/6 the valuation of other companies in its sector.

At the time, it seemed like a home run to me. Katapult didn't have to crush it. The company didn't really have to do anything special. BNPL was hot, Katapult was cheap, growing, and profitable, and I figured that this valuation gap would close as time went on.

So I invested a lot of money in Katapult, and I wrote a detailed piece about the stock on Seeking Alpha.

The piece was so good that it was selected as an Editor's Pick! This was great! My piece got more circulation than normal, a ton of people commented and messaged me about the stock, and I exchanged notes with other investors.

I was confident that my large six-figure position would pay out well over the next few months.

As it turns out, I couldn't have been more wrong. One month after I published this piece, Katapult had their Q2 earnings call.

Management had grossly (AND I MEAN GROSSLY) overstated 2021's earnings projections. They missed revenue and EBITDA forecasts by 30%, and they dropped their forward guidance for the next two years. The stock was cut in half, and by market open I had lost $150,000 in one hour.

Looking back, going balls deep on an unknown BNPL company whose biggest partner was Wayfair (a total Covid beneficiary) was really, really stupid. But no one thinks what they are doing is stupid while they're doing it. It's only after the fact that you think, "Wow, that was pretty stupid."

This one was really, really stupid though.

When you have a $60k salary and you lose $150k, it doesn't feel great. But that wasn't my biggest concern. My chief concern was that the article that I wrote about Katapult had been viewed by tens of thousands of people, and I had told dozens of friends and acquaintances about this stock.

I knew there was a pretty good chance that at least a few of them had invested money in this company because of me. Which means that they lost money because of me.

The one silver lining is that I lost more (either in total dollars or percent of my portfolio) than anyone else on this trade. I certainly suffered the consequences of my conviction. But the fact remained that other people still lost money on my recommendation.

This was a defining moment in my writing career, as I came to two realizations:

I'm not a market genius, I'm just a guy who played a hot trend well for a while

I am a convincing writer who can explain my arguments well

The combination of these two points meant that I could explain a dangerously stupid idea in a dangerously convincing manner, and people who followed my dangerously convincing explanation of a dangerously stupid idea might invest and lose a ton of money as a result.

So I quit writing about individual stocks.

Don't get me wrong, I still have opinions. But opinions are much different from recommendations. I think Tesla is probably overvalued, but I'm not going to tell you to short it. I wouldn't bet against Zuck, but I'm not going to tell you to load up on Facebook Meta. There is too high of a chance that my ideas are wrong for me to give a public, persuasive recommendation about a security, even if I end with a disclaimer that says "this is not investment advice." Because let's be real, most stuff that says it isn't "investment advice" is, at least indirectly, investment advice.

Opinions and Calls to Action

There is a massive difference between saying, "I like this asset" and "You should buy this asset."

Take Tesla, for example. Say I, Jack, think that Tesla is overvalued, and someone else, Mike, thinks that Tesla is undervalued. That is a perfectly normal characteristic of markets! Mike and I can debate our opinions on the stock, and we will probably both learn something in the process! Then we will act according to our beliefs. You have buyers and sellers that act on their opinions, and over time, millions of these actions made by millions of market participants create the price discovery process. This is a good thing.

Now say that I, Jack, am a fairly influential finance personality, and I have a massive short position on Tesla. And I really want the price to go down. So I start tweeting as much negative content about Tesla as possible. I schedule time on CNBC to attack Elon Musk, diss Tesla, and tell everyone that they should sell the stock because it's obviously going to zero.

Well that would be a bit inauthentic, wouldn't it?

The Golden Age of Grift

If you follow me on Twitter, you've probably noticed that I have been vocal about bitcoin and crypto lately. It's no secret that I am a crypto skeptic. That being said, I believe investors should be able to invest in whatever they want.

There is nothing dishonest or "wrong" with buying bitcoin, NFTs, individual stocks, or any other asset that you like. It would be a slap in the face of free markets to prevent anyone from buying any of these things.

There is nothing wrong with us having polar opposite ideas about an asset; that is a necessary feature of markets.

What is wrong is spending your time and energy trying to convince as many people as possible to act in a way that will be financially beneficial to you, regardless of whether it will benefit them.

What is wrong is giving "financial advice" that directly benefits the advisor more than the advisee.

And man, have we seen an influx of "financial advice" lately.

In March 2020, fund manager Jeff Ubben proclaimed that Nikola Motors was the "next $100B company." Ubben's firm happened to have a $154M investment in the EV startup, so they did quite well when the company's stock price increased by 9x in two months! It was later revealed that the "next $100B company" had lied about... pretty much every bit of its technology.

On March 18th, 2020, Bill Ackman went on CNBC and gave an emotional, tear-filled speech where he proclaimed that "Hell is coming" due to the coronavirus pandemic. Less than a week later, Ackman netted a $2B profit when he closed a large short position. He proceeded to invest the profits in some of his firm's portfolio companies like Hilton, Lowe's and Restaurant Brands. Interesting move for someone who thought America as we know it was coming to an end.

On October 22, 2021, when bitcoin was $61,000, Anthony Pompliano told his audience of 1M+ that "If you’re a shareholder in a publicly traded business & they don’t have bitcoin on their balance sheet, it is time to start demanding it. They are complicit in the destruction of shareholder value as long as we have persistently high inflation."

This was followed by the launch of an online course in December literally called "Orange Pill Your Family." Nothing screams prudent personal finance practices like peer-pressuring your grandma into buying some internet money over Christmas dinner.

Bitcoin has declined by 68% since that point, and Pomp went on Fox Business earlier this week to proclaim that this price decline was simply "weak hands selling to strong hands." Which sounds great, unless your orange-pilled grandma lost 68% of her investment. Diamond hands, grandma. Diamond hands.

Michael Saylor is the CEO of Microstrategy, a tech company whose sole purpose is now issuing debt to buy Bitcoin. In March 2021, when Bitcoin was $56,000 per coin, Saylor advised retail investors to sell everything and buy Bitcoin. If they didn't want to sell some of their assets, they should take out a mortgage on their house and pour all of the proceeds into Bitcoin.

Anyone who took this advice would be down 66% on their investment in the "hardest money ever created," and that house would be gone.

Line Goes Up

Some assets go up because the quality of the asset becomes more valuable. Companies that exponentially grow their earnings and cash flows over time tend to become more valuable. Real estate in fast-growing metro areas tends to become more valuable.

Some assets just go up because more people buy them. We often call these assets "bubbles."

The difference between the two groups?

Good investments outperform regardless of promotion. Poor investments outperform because of promotion.

Apple didn't outperform over the last 20 years because silver-tongued investors gave eloquent speeches on prime-time television. Apple outperformed because the iPhone is a killer product. The opinions of bulls and bears were irrelevant over time. You didn't "have to buy it." Apple didn't need you, or me, or anyone.

So what about the stuff that you "have to buy?"

Obi-Wan Kenobi once said, "Only a Sith speaks in absolutes." If someone is telling you that "you have to invest in XYZ," it should raise red flags.

Most of the time, someone saying that you "have to invest" has a financial interest in "having you invest." Because having you (and everyone else) invest will make their price go up. And if you don't invest, that price will probably go down.

Note the difference between "I like the investment because of ______" and "You have to invest because of _____."

The former is a logical argument that lets the audience draw their own conclusions. The latter is an emotional appeal designed to influence an investment decision. Emotions and investments rarely mix well, but emotion plays a critical role when promotion is the objective.

When the value of an investment is driven less by improvement in the fundamentals of the underlying asset, and more by an increase in the number of people investing, it is really important to promote the investment! Someone has to serve as exit liquidity, after all.

"Hell is coming."

"Orange pill your family."

"Mortgage your house and buy Bitcoin."

What does this language sound like to you?

Nobody is going on CBNC saying that you have to invest in Microsoft to avoid the financial apocalypse, are they?

With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility

Sharing your opinion is fine. Bullish on the economy, bearish on the economy, bullish on airline stocks, bearish on energy stocks. Whatever. But when you actively tell your audience that they have to invest in something, then you have to take responsibility if it blows up in their face. And the bigger your audience, the bigger your responsibility.

I don't write about individual stocks anymore because I don't want to influence an investment decision that costs someone else money. Yet from CNBC to Twitter, promoters unashamedly shill their favorite investment ideas every single day.

From promoting a fraudulent EV startup to promoting bitcoin at its peak, figures with large followings continue to use their platforms to pump their investments, often to the detriment of their audiences.

At the end of the day, whether stocks and cryptos go up or down, the players with the large platforms will be fine. But the everyday investors who trust them...

Who buy Nikola because you convince them that it's the next Tesla...

Who pour their savings into bitcoin because you convince them it's the only way to avoid financial ruin...

They are the ones who get hurt when these "investments" fall apart.

And it sucks seeing this happen over and over again.

Of course, none of this was investment advice, right?

- Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!