Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

By 2001, just nine years out of college, Kyle Bass had established himself as one of the most ambitious young faces in finance. After a two-year stint with Prudential Securities, Bass joined Bear Stearns as a stockbroker in their Dallas office, where he flew through the ranks, reaching senior managing director before his 29th birthday.

Legg Mason took notice, and in 2001, the asset management giant signed Bass to a five-year contract to build their first institutional equity office in Texas.

Four years later, after Legg Mason sold a portion of Bass’s business, he struck out on his own, raising $28M and investing $5M of his own capital in 2005 to launch Hayman Capital Management.

Soon after launching Hayman, Bass traveled to Roses, Spain, for a wedding, where an acquaintance suggested that he meet a certain senior executive from the Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs) group of a large brokerage firm.

In said meeting, Bass was shocked to learn that US pension funds and insurance companies had stopped buying tranches of BBB and BBB- subprime debt two years earlier (read: US institutions thought they were too risky), so banks had created CDOs to sell the riskiest tranches of this debt, in bundled instruments, to international buyers.

Bass, sensing a bubble, hired private investigators to determine how easy it would be to obtain a mortgage in the US. Through his investigation, Kyle discovered that half of all applicants were overstating their incomes by more than 50%, but they were still being approved because mortgage lenders were far more concerned with quantity than quality.

Basically, plumbers making $40,000 were taking out mortgages to buy $500,000 houses. The whole thing was a tinderbox ready to blow.

So Bass called his shot, purchasing $110M in credit default swaps in a bet against the real estate market.

And he was right.

In December 2007, the investor was introduced on Bloomberg TV as a man who had just made a fortune “basically betting against the subprime borrower,” after parlaying that $110M bet into a $700M profit.

Bass’s flagship fund generated 212% returns for investors in 2007, and the fund manager became one of the hottest names on Wall Street. Michael Lewis wrote a chapter about him in The Big Short, Congress called him in to testify, and he was a mainstay in financial media for years after the housing market failed.

But Kyle Bass wasn’t done. In fact, he thought the subprime mortgage crisis was just the canary in the coal mine forecasting a larger global currency and debt collapse.

After striking gold in 2007, Bass, on the hunt for the next crisis, has placed outsized bets against Greek and Japanese debt, the yuan, yen, and the Hong Kong dollar. He believed that Greece’s debt problem was “inescapable,” Japan’s central bank policy would create a hyperinflation spiral, and China’s banking system was a cheap facade waiting to collapse.

But then a few funny things happened.

Bass was one of many speculators in 2012 who assumed Japan would be forced to raise their rates, thus causing a decline in bond prices, any day now. But he was a decade early. The BOJ didn’t touch their interest rates until December 2022, by which time Bass had already lost money on this trade and exited the position.

Bass next tried to short the Japanese yen, predicting that a hyperinflation spiral would send it to a 200:1 exchange rate with the dollar. While the yen did decline from a record high in 2012, it simply returned to its historic range, trading at the same level in 2015 as it had in 2007.

The Chinese banking system still hasn’t collapsed either, and Hayman’s Hong Kong dollar short trade lost 95% of its value.

In fact, Bass’s only correct macro bet after the housing crisis was his Greek debt short position, which returned his fund 16% in 2012, while the S&P 500 generated a 13.4% return. Hardly outperformance.

And while Bass continued calling for the next collapsing regime, the S&P 500 just kept climbing, generating a 15.33% CAGR between January 1, 2009 and December 21, 2019.

Many investors, tired of years of underperformance, ditched Hayman Capital, and its flagship fund’s discretionary assets under management declined from $2.1B in 2014 to $524M in 2019.

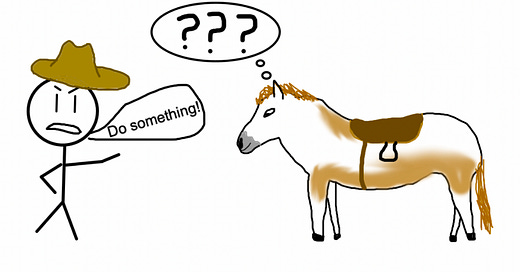

Kyle Bass was a one-trick pony who called the housing market collapse in 2007, and he hasn’t had another big hit since. But Bass wasn’t an outlier. In fact, history shows that most investors who nail a home run trade underperform afterward.

Crispin Odey made a fortune betting against European sovereign debt, but he hasn’t hit it big since.

Cathie Wood was the hottest name on Wall Street two years ago, but her flagship Ark fund has declined by 70% since “disruptive innovation” fell out of style.

Michael Burry, the most famous winner of The Big Short, now tweets an ominous doomsday stock market prediction every few weeks, just to delete his account when his forecast fails to materialize.

The list goes on and on.

I have a few thoughts on this.

First, when you make a very significant amount of money through a very specific opportunity in a very short amount of time, you begin to look for that same opportunity everywhere. If you made billions shorting the imminent collapse of the housing market, you’ll begin to see “imminent” collapses everywhere, from European debt crises to Asian central banks. If your bet on disruptive innovation returned 200% in 2020, you won’t think, “Oh man, these stocks are overvalued now. Let’s change it up.” You’ll think, “I was right. Let’s find some more disruptors.”

Second, it’s impossible to weigh the impact of luck vs. skill in these home run trades. Bass was right about the housing market collapse, but what if it didn’t happen until 2011? 2014? Would his investors have stuck with him? Would he have run out of money? He was right about the Bank of Japan too, but he was ten years early. And in this game, if you’re early, you’re wrong. Skill can help you develop a thesis, but you need a little luck to nail the timing. But when you spend months planning a trade, and you just know that it’s going to hit, and you’re proven right, you ignore luck and attribute all of the success to your prowess.

Third, everything is cyclical. Tech stocks and value stocks fall in and out of style. Different sectors and assets, from AI to crypto, explode before flaming out. Investors get greedy as stocks climb by 100, 200, and 300%, and they grow fearful as these same stocks decline by 50, 75, and 90%.

Investors that generate outsized returns in a short period of time tend to do so by catching inflection points in markets, and by the time they’re ready to make the next trade, those market conditions changed. The very thing that worked so well once is likely a horrible strategy just a year or two later.

And finally, hubris is one hell of a drug. No one knew who Kyle Bass was when he launched a $33M fund in 2005. No one knew who Cathy Wood was when she launched Ark in 2014. But after the housing market collapsed in 2007, and after Tesla 10x’d in 2020, Bass and Wood became two of the most popular figures in finance. Bloomberg and CNBC praised Bass as one of the only investors smart enough to identify and capitalize on the housing bubble, and these same networks drew comparisons between Wood and Buffett as her ETFs generated market-leading returns.

And it feels good to be “the man” (or in Cathie’s case, “the woman”). To have the rest of the industry look up to you with a mix of awe and jealousy. And you want to stay in the limelight, to retain that attention. And this desire for attention entices investors to continue making bets that will keep them in the limelight.

After generating 212% returns in 2007, Bass could have invested his entire fund in the S&P 500, kicked back, chilled, and enjoyed those sweet, sweet 15% annualized returns for the next decade. But Bass made a name for himself by profiting from a crisis, so he spent the next decade looking for the next crisis.

The players and trades change, but the story stays the same.

- Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!

Jack's Picks

Doug Boneparth wrote about the most dangerous types of “investing gurus” that you’ll find online.

Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella explained why he thinks AI can beat Google in this interview with The Verge.