Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

If you are addicted to social media (I am), you probably saw a certain "net worth" TikTok make the rounds last week.

If you don't want to watch this embodiment of pure cringe, I'll give you a quick summary:

Guy with $500k net worth (really cool!) goes on a date night with his wife. He repeatedly checks his ($500k) net worth at dinner to ensure they are still on track for their portfolio goals, before ordering two $13 cocktails.

Seriously.

Our man was quite proud of his fiscally responsible decision-making. I imagine if the market had been red that morning, his wife would have been stuck with a ham sandwich and water for dinner.

This video was (rightfully) dunked on across social media, but this dude's behavior isn't as farfetched as it first appears. While most of us aren't basing our date night budgets on the intra-day movements of the S&P 500, we are guilty of more subtle examples of this same phenomenon:

The overfinancialization of everything.

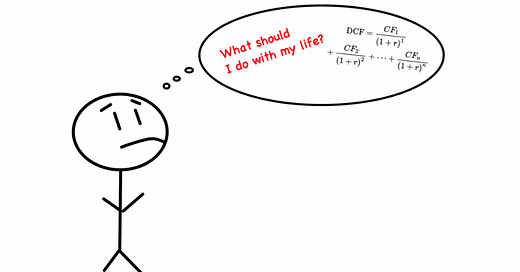

As many of you know, I'm in business school right now. The decision of whether or not one should attend graduate school is quite common for mid-to-late 20-somethings these days, but how does one figure out what they "should" do?

Typically, we ask if it makes financial sense.

Many of you are probably familiar with discounted cash flows, or DCFs. For those who aren't, DCFs are financial models that we use to estimate the value of a company now based on our projections of a company's cash flows in the future. You model estimates for cash flows for X number of years, and you use a "discount rate" to calculate what those future earnings would be worth in today's dollars.

In layman's terms, a DCF can model the current value of your future earnings in different scenarios.

Oftentimes, especially for people already working in high-paying jobs, the math says "No!" to graduate school. If you are making $150,000 per year for example, why would you abandon two prime working years to take on $100,000+ in debt to go back to school?

The numbers just don't make sense.

This isn't just a grad school thing. From high school onwards, our lives are structured as living, breathing DCFs.

Where do you go to school? The place that will cost the least and/or help you get paid the most after you graduate.

What do you study? The major most likely to land you a high-paying job. Which companies should you work for, promotions should you pursue, cities should you live in?

Whatever makes you the most money, money, money.

Now don't get me wrong, weighing the financial pros and cons is both an important and frugal step to take when making any big life decision. But financial pros and cons are far from the only variables we should take into account.

A DCF may help you estimate the financial impacts of your decisions, but it can't help you weigh the importance of these financial impacts. It may help you find the path to make the most money, but it won't help you use your money to walk the best path. The nonfinancial tradeoffs are invisible.

Zoom out.

The overfinancialization of everything is a disease that makes us slaves to our success. The opening to Aaron Tang's most recent piece gives a damning anecdote of this very experience.

Hetty Green was the richest woman in America. It was the 1900s, and despite living in a male-dominant age, she was a centimillionaire — seen as a peer to tycoons like J.P. Morgan, Andrew Carnegie and John Rockefeller. Just looking at the numbers, many would consider her a great success.

Alas, if you’ve heard of Hetty before, you probably know her for something else. The Guinness World Book of Records calls her the “World’s Greatest Miser.” Legend has it she never turned on the heat, wore shabby old underwear, and when her son Ned broke his leg, sent him to a free clinic for the poor. Poor Ned eventually had to have his leg amputated.

Hetty Green had F.U. money, but I imagine she was not very happy.

Aaron Tang

All the money in the world, and what did she have to show for it?

Perhaps if money was the sole driving force in our lives, and perhaps if we lived in some dystopian Black Mirror episode where the highest calling was the creation of shareholder value above anything else, the overfinancialization of everything would make sense.

But you aren't the CEO of your life's corporation, and you don't have to maximize your net income or shareholder value. Profit isn't the goal, it's a tool to help you realize your goals.

Before asking what path makes the most money, you should decide what you want the money for. What path do you want to take? How will the money help you get there?

A DCF can't calculate the value of novel experiences and good friends. It may reveal the most lucrative career path, but it obscures the non-monetary cost of those high earnings. And the non-monetary costs are what really move the needle.

- Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!

Jack's Picks

Here is Aaron Tang's whole piece that I referenced earlier. It's a great read on finding satisfaction.