Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

Personal Anecdote on “Jobs”

If you’ve been following my travel blog (link at bottom of this post), you know from my last post that I just started a new job writing for the face of finance, Litquidity:

Not the career path I imagined two years ago. As a college student, I was furiously applying to every finance job in Atlanta: UPS. Norfolk Southern. Home Depot. Delta.

If it was a billion dollar company hiring entry-level financial analysts, I probably applied for a position. Why? Because like any other finance major with a decent GPA, I was supposed to follow this career progression:

Entry-level financial analyst

Promotion(s)

MBA

Higher paying job in consulting or finance

Promotion(s)

Retire

Unlike previous generations of finance students, I started my career in March 2020. COVID also hit the traditional work environment like a freight train in March 2020. I grew bored of staring at spreadsheets in my apartment everyday, so I pursued other healthy interests like making and losing hundreds of thousands trading SPACs in my Roth IRA, posting about these SPACs on Reddit, publishing detailed stock write ups on Seeking Alpha, and writing finance satire.

18 months of doing a lot of random stuff showed me two things:

I don’t want to follow the “traditional” career path anymore

I can make a lot of money by not following the “traditional” career path

I’m supposed to be helping build UPS’s profit plan right now, but instead I’m sitting in Dundee, Scotland, writing this article. Fate loves irony I suppose.

But enough about me. I am one of thousands that now considers themselves part of the creator economy. More than a trendy buzzword, the creator economy is a permanent shift in labor markets. Let’s dive in.

What Is the Creator Economy?

Writers on Substack are the creator economy. Small businesses on Shopify are the creator economy. Landlords on Airbnb are the creator economy. Free-lance drone photographers, TikTok stars with millions of followers, dog sitters advertising on Facebook, and anyone else making money doing their own thing outside of the traditional corporate structure is part of the “creator economy”.

The creator economy isn’t new, but the barriers to entry used to be much higher. Pre-internet, information traveled slowly. You could communicate face to face or over the phone, and TV and radio advertisements were viable options as well. However, face to face and phone communication are slow (one on one, over and over again), while advertisements were expensive. The internet, and social media specifically, changed everything.

Transfer of information used to be linear: point A to B, rinse, repeat. With the internet, information now expands exponentially from a central point.

The costless, instant flow of information has created an environment ripe for individuals to build their own businesses. However, higher education is still structured to favor traditional work. You major in finance to be a financial analyst, or engineering to be a mechanical engineer, or accounting to be an accountant. Career service centers at universities help kids construct resumes to appeal to large employers. Internships with Fortune 500 companies are highly coveted.

Why?

Because for decades, this was the sure-fire way to succeed.

COVID-19 changed everything. Every white collar job in America went remote. Suddenly, every employee and employer realized they didn’t have to be in the office to get their work done. Employees had opportunities to explore other interests during work hours. While this may have been frowned upon in the office, no one really knows what you’re doing from the comfort of your own home.

Some workers realized these other interests could be lucrative. The infrastructure for the creator economy has existed for years, but a pandemic-induced lockdown kicked it into overdrive.

Betting on Yourself

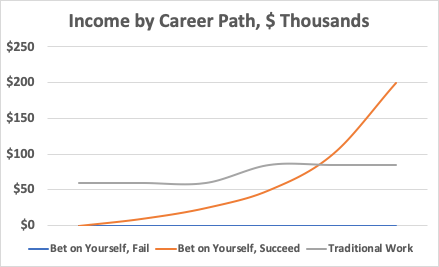

There is a risk/reward sliding scale for careers. Traditional careers offer stability. If you’re a financial analyst for Home Depot, you’ll make $60k a year. That’s a steady paycheck coming in every two weeks. If you suck at work one week, you get paid ~$1200. If you’re really good, you get paid ~$1200. If you compound the good weeks long enough, you’ll get a promotion. Then you make $85k, with another slightly higher steady paycheck.

At the opposite end, there’s the pure free-lancer. The writer who monetized his blog. The programmer who only works as an independent contractor. The Tiktok star with a massive following. If they have a bad week, they don’t make money. If they several bad weeks, they don’t have money.

That’s the risk component. However, high risk is typically associated with high potential reward.

Salaries provide stability, but they also create ceilings. $60k is your floor, but it is also a temporary ceiling (excluding bonuses). Your floor and ceiling increase as you move up, but they still exist. Even at the highest levels, there is only so much money that you will make in salary. There are also only so many high level positions in an entire industry. You could be an exceptional VP of finance for your company, but if the CFO is 45 years old with no intentions of retiring soon, there isn’t any more room to move up. Once your talent exceeds your income ceiling, your income reaches a cap.

The individual working for herself has no ceiling. If you run a successful YouTube channel, you can make $100k. If you have one of the most popular channels in the world, you can make millions. If you’re a commercial real estate analyst for CBRE, you could make $150k. If you build your own real estate portfolio, you could make $15 million.

You get the idea. Those who strike out on their own assume all of the risk, but they also reap all of the rewards. It’s the ultimate meritocracy: if you create good stuff, you’ll get paid. If you don’t make it, you can’t blame anyone but yourself.

Betting on yourself is more than choosing a high risk, high reward over the alternative. Betting on yourself is an asymmetrical bet. The worst case scenario of striking out on your own in making $0. Even if you never make a dollar, you’ll gain invaluable experience that will help you land another job. If you’re young and have no dependents, the risk in taking a risk is almost nonexistent.

When you have limited downside and unlimited upside, you have an asymmetrical bet. In finance, we love asymmetrical bets.

Why Don’t People Bet on Themselves?

I thought this tweet from Ryan Hoover was spot on.

“…According to him, his job keeps him too busy, and he can never find enough time to write novels, and that’s why he can’t complete work and enter it for writing awards. But is that the real reason? No! It’s actually that he wants to leave the possibility of “I can do it if I try” open, by not committing to anything.”

We take solace in the “what ifs” because they let us envision the idea of success while avoiding the harsh reality of failure. Ironically, the biggest failure is never taking those risks in the first place.

Betting on yourself is hard and scary. But not betting on yourself is worse. What ifs about the future are fascinating, because they represent dreams of what you hope to achieve.

As time goes on, future what ifs become past what ifs. These past what ifs are suffocating, because they represent the dreams that you never pursued, and now you’ll never know.

Everything in life, including indecision, is a choice. I’m no philosopher, but I do know that the biggest regrets in my 24 years are regrets of omission, not action.

That being said, betting on yourself is going to suck for a while.

How Long Are You Willing to Suck?

You are going to suck at anything when you’re just getting started. Writing. Vlogging. Playing a sport. Cooking. Running your own pet care service. Trading stocks. Speaking a foreign language.

My friend Tucker Cannon is a pretty good trader. He has been steadily compounding anywhere from $500 to $5000 a day for weeks now. The only reason he’s good now is because he sucked for months. He had some lucky hits early on, reaching $80k. Then a series of emotional mistakes caused him to lose $50k.

After getting wrecked, he spent months studying price movement and volume patterns and tracking “paper trades” (using fake money to emulate live trades) before going live again. He now has a disciplined system that he follows religiously, and the small gains are quickly compounding.

I like writing. I write two blogs for free, and I recently got hired to write for someone else. I also sucked at writing for a while. Here’s a list of writing/investing positions that rejected me over the last year or so:

Social Capital (Chamath Palihapitiya’s company): 2x

Morning Brew: 3x

The Hustle: 1x

Truist Bank: 1x

UPS: 1x

Roundhill: 2x

Titan: 2x

0-14 is a poor record, but it’s not the cold rejections that suck. It’s the opportunities that are within reach. The ones where you excitedly tell your friends that you’re about to land an awesome gig.

The ones where your proposal positions you, an active SPAC trader, as a finalist to work for the top SPAC sponsor in the market.

The ones where you make the final interview with a cool group of guys that are leading the charge of thematic ETFs.

The ones where you are one step away for working under your favorite author.

I was a finalist for all three of these positions. I went 0-3. The hardest aspect of rejection isn’t missing out on the position. It’s acknowledging that no one owes you anything, and someone was better than you. And then continuing to work.

Several months later, I’m 1-14. You know why I landed that 1? Because I wrote a lot. You know why Tucker makes money trading? Because he traded a lot. You know why anyone gets good at anything? Because they do that thing a lot.

The willingness to suck is a superpower. Two things happen if you suck long enough:

You get better

Most of the competition drops out

If you can suck long enough, success is damn near inevitable. Most people just aren’t willing to suck.

Choose Your Struggle

It is difficult to succeed in any field. Professional athletes spend tens of thousands of hours honing their craft. Premiere defense attorneys have to be world-class investigators and debaters. Famous authors publish millions of words. You get the idea.

If you want to win, you will have to struggle. Luckily, you do get to choose your struggle. Most young people learn how to win (i.e. advance their careers), but not what to win. That’s why countless Ivy League graduates pursue jobs in investment banking or consulting. These industries leverage prestige, lucrative salaries, and the promise of future career optionality to lure thousands of high achievers who aren’t sure what they want to do.

The creator economy provides an outlet for the high achievers who want to choose a different struggle. Would you rather grind 100 hours a week as an analyst for McKinsey & Co, or spend 100 hours cultivating your own work?

It’s going to be a grind either way, so select your grind accordingly.

Closing Thoughts

The creator economy has turned the labor market on its head. You no longer have to work for Bloomberg or Forbes to make a living writing. You don’t have to work for a hedge fund or investment bank to trade stocks. You really don’t have to work for anyone else at all if you can create something great. The possibilities are endless.

That being said, it’s going to be really, really hard. But it’s going to be really, really hard to get good at anything. So if success is going to be really, really hard no matter what, you might as well grind at the thing that can pay you the most, on your own terms.

Obviously I’m bullish on the creator economy, but this isn’t some call to action for a mass exodus from the job force. Stable careers are a good thing, especially if you have responsibilities like a spouse, children, mortgage, etc. I don’t have those things, so I’m more flexible than most. If you’re like me, and you don’t have other responsibilities, there has never been a better time to take that risk. At worst, you make $0, gain valuable experience, and land another job in six months. At best, you can do whatever you want.

I’ll take that bet every time.

- Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!