Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

What is Risk?

Let’s rewind the clock to 2019. I was a senior in college, and my business school played CNBC in the lobby each morning. Every day, as I walked to my 10:00 AM Mergers & Acquisitions class, I would stop in the lobby to glance at the media headlines.

Trade War with China Could Increase Import Prices!

Tensions Rise between Donald Trump and Kim Jung Un!

How Will Brexit Complicate Trade between Europe and the US?

China Trade War. North Korea tensions. Brexit.

Three powerful stories that, at the time, I thought would have massive implications in both geopolitics and financial markets through the 2020s.

Unknown to me in 2019, someone in western China had just lost their sense of taste, and four months later the world would be locked down. Two years after that, Russia invaded Ukraine, marking the most dangerous act of aggression in Europe in decades.

In hindsight, risk wasn’t the trade war with China for which we were drafting legislation, risk was a virus emerging from China for which we had no cure.

Risk wasn’t the UK leaving Europe by democratic means. Risk was Russia entering Europe through shock and awe.

Real risk isn’t in media headlines. Risk isn't heavily talked about.

Risk is all of the outcomes left over after we think we have prepared for risk.

As Morgan Housel says, “Risk is what you don't see.”

Two Facets of Risk

Risk can be divided into two categories:

Fast risk: The long-tail, low probability risk that rarely happens, but shocks the world when it does. 9/11, Covid-19, Chernobyl and other singular events that seemingly appear out of nowhere are fast risks.

Slow risk: Risks that compound, or grow, over time due to our actions and inactions. Visualize a snowball rolling down a mountain that eventually becomes an avalanche. Lung cancer from smoking and aging populations from low birth rates are slow risks.

What is important isn’t necessarily the risks themselves, but our actions surrounding these risks.

Fast Risk

Climate change is the world’s most well-documented existential threat. As global temperatures have continued to rise, companies across all industries have vowed to go carbon neutral. Meanwhile, EV adoption has exploded as consumers want to reduce their emissions.

For years, Germany appeared to be leading the fight against climate change: in 2000, more than 30% of their energy came from nuclear power.

For those curious, nuclear power is, unequivocally, our best form of “green energy” right now. No emissions, minimal physical space required, and safe.

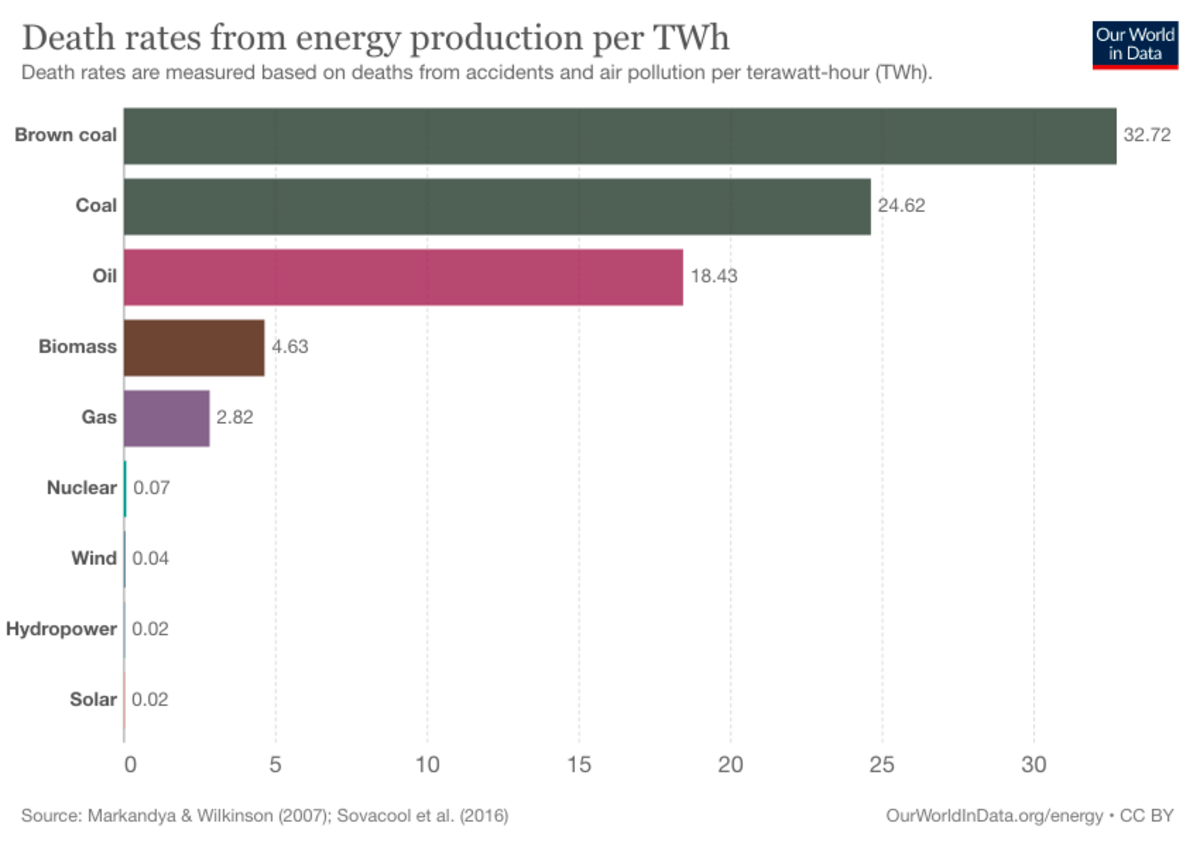

How safe is nuclear power?

263x safer than oil, if we using deaths per TWh produced as the metric.

Note that this data includes both Chernobyl and Fukushima; if you exclude two data points, nuclear is the safest energy on the planet.

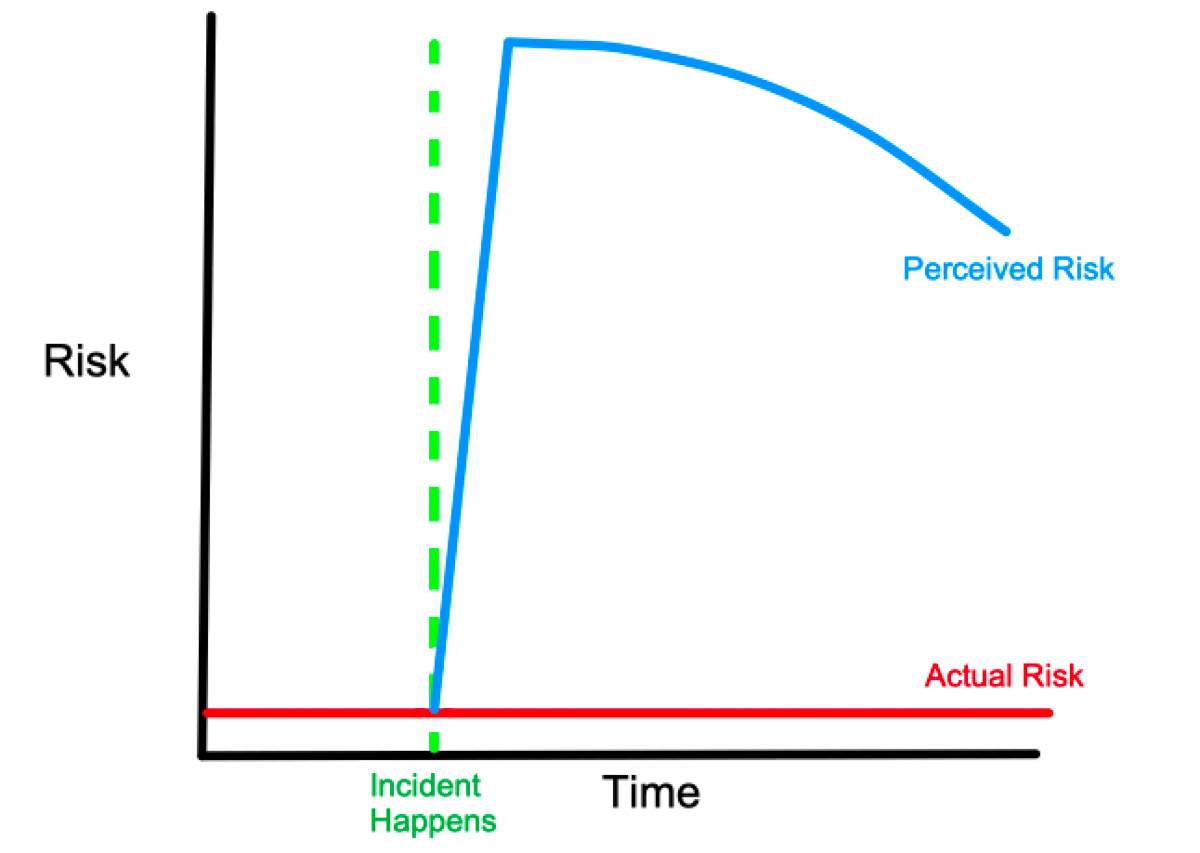

This data is contrary to popular belief. The phrase "nuclear power” evokes images of Chernobyl, hazmat suits, and yellow-and-black triangular signs. The risk of a reactor meltdown feels terrifying, as we have seen just how damaging these meltdowns can be.

A decade ago, the Fukushima reactor in Japan melted down in the worst nuclear disaster since Chernobyl. However, it never should have melted down. The plant’s operator, Tokyo Electric Power Company, had failed to meet basic safety requirements, notably risk assessment. Overlooking these safety protocols didn’t matter, until it did.

In 2011, an earthquake-induced tsunami hit the facility. The reactor should have shut down, but thanks to negligence by the TEPC, the reactor melted down instead. 150k people had to be evacuated as a result.

In the wake of Fukushima, Germans were up in arms about the dangers of nuclear power. Fears of radiation poisoning and reactor explosions fueled protests across the country, and the movement to denuclearize German grew.

What this movement missed, however, was 1) just how unlikely the odds were of a German reactor meltdown, and 2) where the country would turn for an energy alternative.

A nuclear meltdown, by itself, is an incredibly rare event. On top of that, nuclear power worldwide was even safer after Fukushima, as it caused other nuclear plants to review their own safety protocols.

Germany, a central European nation with minimal seismic activity, is not at risk of earthquakes and tsunamis. Every reactor in the world has safety standards and technology magnitudes better than Chernobyl in the 80s. Germany, known for its meticulous attention to detail and expert engineering, had the best nuclear facilities in the world.

Thus, there was a huge disparity between perceived and actual meltdown risk in Germany.

However, politicians eventually caved to the populace, and the German government made plans to close every nuclear plant in the country.

This energy deficit had to be accounted for with new power sources, and neither wind nor solar were anywhere near developed enough to close the gap. Germany turned to importing coal, oil, and gas from Russia.

Yes, a country wanting to fight climate change made the conscious decision to replace its domestic clean energy with imported fossil fuels from another country.

As a result, German clean energy took a step back, and the country’s power grid was at the mercy of Russia.

Still, Germany was chugging along just fine… until Russia decided to invade Ukraine. The EU issued sanctions against Russia, but Germany was in a tight spot: they needed Russian fuel. Sanctions may have been the “right” thing to do morally, but without energy imports, German energy prices would be astronomical. Citizens could very well freeze to death.

Germany’s decision to shut down its nuclear plants 10 years ago, a decision rooted in perceived risk (nuclear meltdown) but not real risk, increased the country’s exposure to a more probable risk (dependence on Russia).

Slow Risk

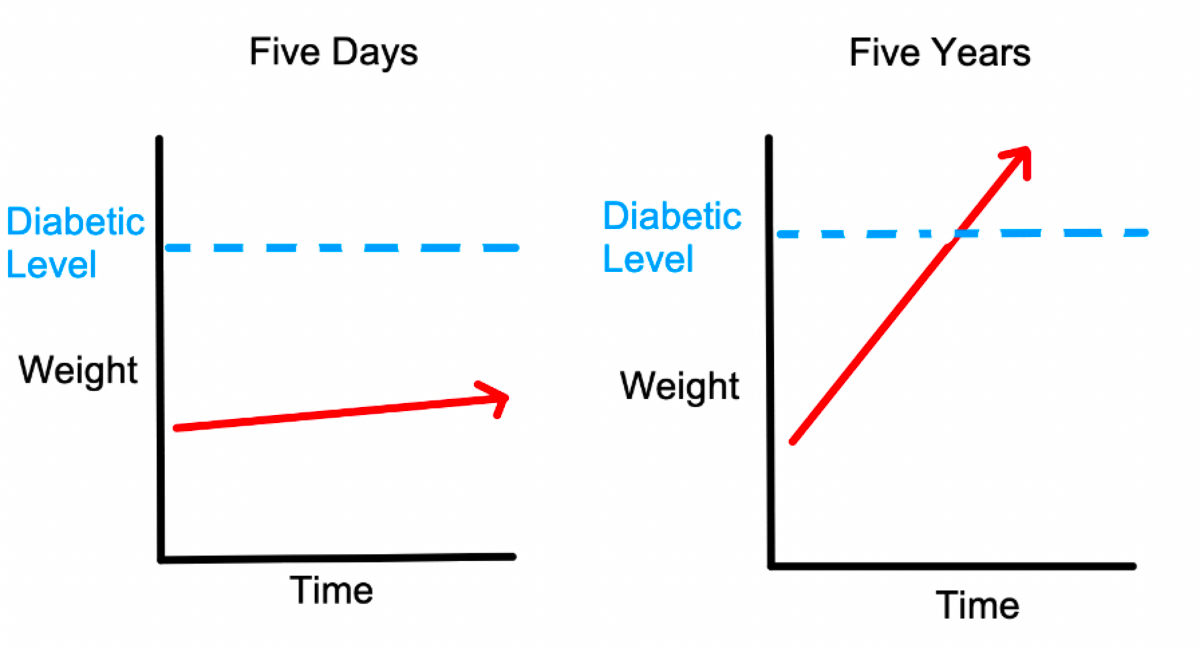

Diabetes is a chronic disease that disrupts your body’s ability to process sugars. Diabetics rely on insulin injections to regulate their blood sugar; without it, their bodies could shut down.

There are two types of diabetes:

Type 1: Typically appears at a young age and has little to do with an individual’s health or habits. A type 1 diagnosis is caused by genetics

Type 2: Emerges later in life as a result of poor health, obesity, low quality diet, etc. A type 2 diagnosis is largely caused by an individual’s habits

According to the CDC, 10.5% of Americans had diabetes in 2020. However, Type 2 (preventable) diabetes was 20x more common than Type 1.

The biggest risk factor for Type 2 diabetes is bodyweight. Obese individuals are 80x more likely to develop diabetes than those with a BMI under 22.

Unlike a nuclear reaction or terrorist attack, diabetes doesn't develop over night. It takes years of weight gain and inactivity for the disease to take hold. You won't notice changes in your body or health from day to day, but years of an unhealthy life will compound.

If you are diagnosed, the treatments for diabetes (outside of taking insulin) consist of lifestyle changes like daily exercise and eating healthier.

Ironically, many diabetics would have avoided diabetes entirely had they made these changes before their diagnosis.

The correct proactive actions and reactive responses to diabetes are identical, yet one prevents the disease while the other merely helps you cope with it.

Fast (Investing) Risks

This article does actually have something to do with your portfolio.

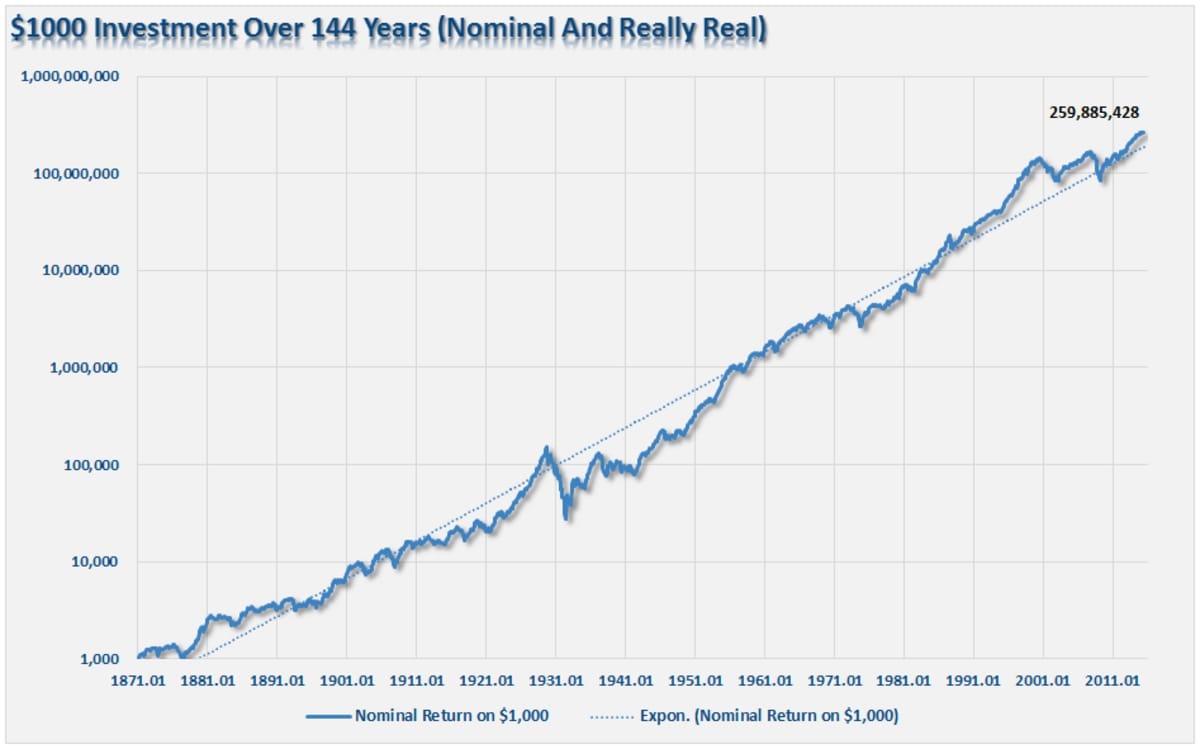

Since the stock market’s inception, it has typically gone up and to the right, except for when it hasn’t. However, the long-term trend IS up and to the right.

We are lulled to sleep by the normalcy of this “up and to the right”, until we have a March 2020. Then the market goes down and to the right, erasing two years of gains in three weeks.

Ironically, this was the best time to invest. This wasn’t 2008, where the financial system almost ground to a halt. This “recession”, if you want to call it that, was caused by a virus. So the physical world shuts down, and we live in a remote-first environment. Who benefits in a remote environment? The biggest companies in the world: Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Facebook.

And you could buy all of them for 30% off.

But when it feels like the world is ending, you aren’t seeing discounts.

You aren’t seeing the big picture. All you are seeing is your portfolio declining by hundreds of thousands of dollars, and it hurts, and you panic.

Because what if it keeps going down? What if the market doesn't bounce back for a decade? What if you can save another $100,000 by getting out now?

So you sell, and never get back in.

But one day, stocks resume their path up and to the right. And you are no longer along for the ride.

After ten years, if you don’t get back in, you miss a decade of compounding. You are in a poorer financial position.

But when it feels like the world is ending, you aren’t seeing clean, low-risk energy. You aren’t seeing the big picture of energy independence. You aren't seeing that issues with foreign reactors don't translate to your domestic reactors. All you are seeing is reports of radiation and hundreds of thousands of displaced citizens, and you shut down your reactors at the worst possible moment.

Though you shut down your reactors out of fear, nuclear technology continues to develop. But you are no longer along for the ride.

After ten years, if you don’t reactivate the plants, you miss a decade of energy independence. You are at the mercy of your energy exporter.

Psychologically, selling at the bottom of a bear market without an investment alternative and closing nuclear plants with no energy alternative are the same thing: fast risk happened, fast risk scared you, fast risk caused a knee-jerk reaction.

And our reaction to fast risk is everything. Selling at the bottom of a bear market can set your retirement back a decade. Closing nuclear reactors after an incident on the other side of the world can leave you at the mercy of your energy provider.

The first reaction is almost never the right reaction when dealing with fast risk.

Slow (Investing) Risks

Month after month, year after year of investing into broad market index funds is the most tried-and-true way to build wealth. You can’t control what the market does on any given day, but you can control three things:

How early you invest

How often you invest

How much you invest

Let’s assume the market averages 9% returns annually over the next 40 years. It might not, but history is in our favor here. How will your portfolio fare in different scenarios?

$100k invested now, no funds added, for 40 years: $3.1M

$560k invested now, no funds added, for 20 years: $3.1M

By delaying a lump sum investment 20 years, you have to add 4.6x as much capital to achieve the same result.

But most people don’t have $100,000 just laying around, so let’s go with something more realistic.

$6k invested each year for 40 years: $2.2M

$39k invested each year for 20 years: $2.2M

By delaying annual investments 20 years, you would have to invest an additional $33,000 annually to achieve the same result.

The difference between delaying your investment just one year is negligible. The difference between delaying your investment 20 years can ruin your life.

Diabetes works the same way. Sure, eating like shit and not exercising for five months won't kill you. But five years can do permanent damage.

And that's what makes slow risk so dangerous; it is impossible to track from day to day, but impossible to ignore from decade to decade.

It's not until you're 20 years down the road that you can say, "Wow, my capital has grown!" or "Shit, I should have invested earlier."

It's not until you're 20 years down the road that you can say, "Wow, I'm glad I stayed in shape!" or "Shit, I should have worried about my health earlier."

It's easier to stay healthy from a young age than it is to try and get back in shape later. It's easier to invest consistently from a young age than it is to get started later.

Fast risks are largely unpredictable; we can only control our responses. Your first response to any fast risk is unlikely to be the best response, so give yourself some time to think the situation through.

Slow risks are predictable in theory, but difficult to observe until it's too late. Slow risks can be mitigated by taking action before they are noticeable.

Happy Friday, let's indulge in some risk this weekend.

- Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!