Welcome to Young Money! If you’re new here, you can join the tens of thousands of subscribers receiving my essays each week by adding your email below.

“Disruptive Growth at All Costs”

Twitter is a fascinating platform because you have constant exposure to investor sentiment in real time. In 2020, one type of stock outperformed all: high growth. Companies that doubled their revenues saw their stock prices increases by 1000%.

Video conferencing company? Moon.

iPad taped to a bicycle? Moon.

Online sports gambling company? Moon.

Streaming entertainment company? Moon.

Every SaaS company ever? Moon.

You throw something about growth/tech/innovation in the company description, and that stock probably quadrupled.

And from the depths of Twitter came a new class of investing “gurus”. Are they licensed securities professionals? Oh no. No no no. But they are individuals who saw that some companies were growing revenue (or projected revenue) quickly. So these individuals bought those stocks. And those stocks doubled, tripled, quadrupled, or whatever in price.

And these investors made a lot of money, and they grew massive followings who also wanted to make a lot of money. And because they all made a lot of money buying high growth stocks, they began looking for new high growth stocks. A entire wave of “long-term” investors looking for 6 month 2x returns was born.

Because 75% of investors on Twitter started investing around… 2020 (myself included), all they knew was growth stocks = moonshot. Revenue growth is good? That’s all the analysis I need, partner. Valuations? There is no price too high for quality. We don’t talk about valuations here.

Efficient markets at work. And none of this mattered.

Until it did matter.

A lot.

2021 was a real slap in the face to the “growth at all costs” fam.

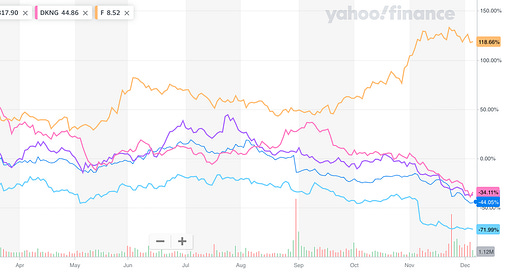

Peloton: -72%

Zoom: -44%

Roku: -38%

DraftKings: -34%

The stock that is up 118%? That’s Ford Automotive. You know, the boomer vehicle manufacturer that is struggling with serious supply chain disruptions.

These are really good companies. But over the last year, they have been really bad investments. Valuations always matter. Entry points matter. And you could buy the best company in the world and not make a dime if you pay too much.

Expansion —> Retraction

What happens when the valuation of a company grows faster than its revenue (or net income)? Multiples expansion. If a $1 billion company is doing $100 million in revenue, it is trading at a 10x sales multiple. If that company doubles its revenue to $200 million, but its valuation increases to $4 billion, it is now trading at a 20x sales multiple.

Expansion!

Cloudflare (NET) is a pretty cool company with a pretty cool ticker. What does Cloudflare do? A lot, actually. To keep it simple, NET is the best cybersecurity company in the world. A lot of businesses use its services, and Cloudflare has only grown more valuable as our world becomes more digital.

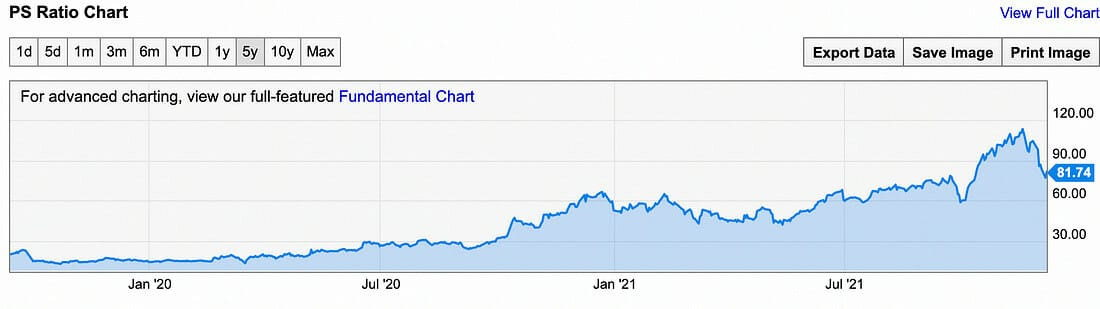

In Q3 2019, Cloudflare did $74 million in revenue. In Q3 2021, Cloudflare did $172 million in revenue. More than doubling revenue in two years is fantastic stuff.

In Q3 2019, Cloudflare was trading at 20x sales. In Q3 2021, Cloudflare traded at 76x sales.

That, my friend, is what we call multiples expansion. But multiples don’t just expand. Sometimes they contract.

Cloudflare is trading at 81.74x sales on ~$600 million in revenue right now. That is really high. Say its revenue doubles to $1.2 billion next year. Is that likely? No. NET’s revenue this year only grew by 50%. but for example purposes, let’s say revenue doubles.

Cloudflare would still be trading at more than 40x sales if the stock’s valuation stayed the same. Still really expensive. Now say revenue doubles, but the software market undergoes a pretty strong multiples contraction. Now Cloudflare “only” trades at 20x revenue (which is still really expensive) after its revenue doubles.

The stock would be down 50%.

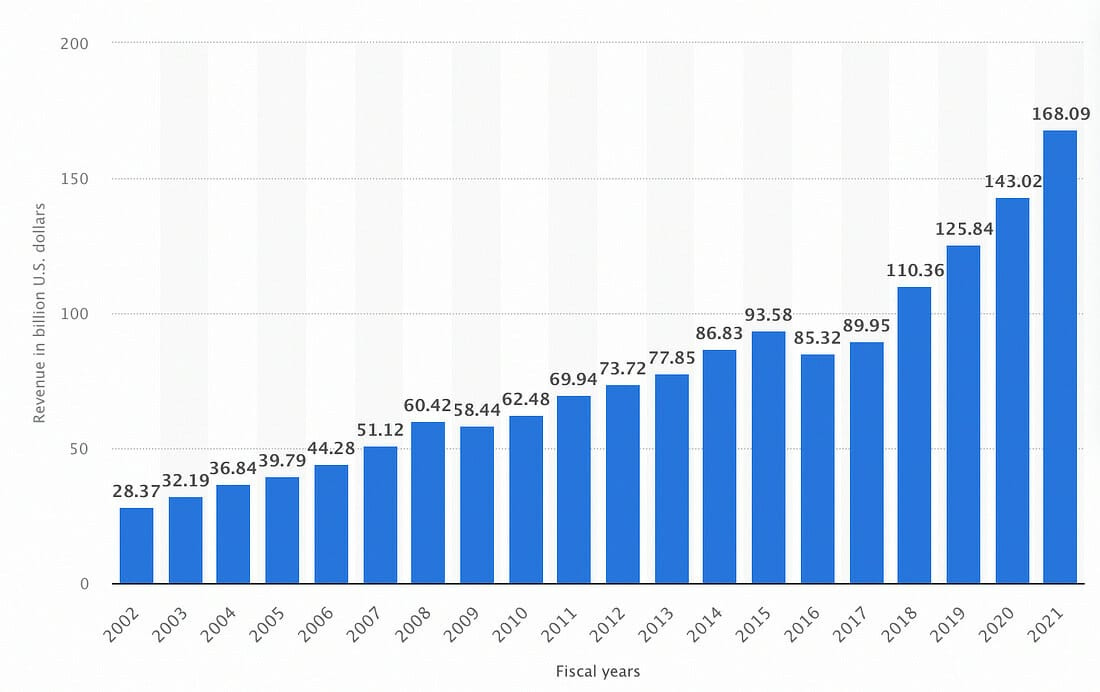

100% revenue growth is nuts, the company is executing on all cylinders, and you would lose half of your money. You don’t believe me? Check Microsoft from the peak of the Dotcom bubble to now.

If you bought MSFT in 2000, you would have waited 15 years to breakeven on your investment.

Despite the fact that revenue more than tripled in that timeframe.

Unfortunately the revenue numbers from 2000-2001 were unavailable. The point stands though.

Microsoft was a well-oiled machine growing its revenue like crazy in the 2000s. But you wouldn’t have made a dime on your investment.

How Much Will You Pay for a Good Story?

Investors have long used metrics such as Price to Earnings to determine the worth of a company. “Oh, Apple is trading at 20x 2021 earnings!”

But some companies aren’t profitable. In fact, they may lose money. But they are only unprofitable because they are reinvesting so much money back into the company. That doesn’t mean the company is “worthless”, Amazon was worth hundreds of billions when it was turning net losses quarter after quarter in 2015.

So we needed a metric other than Price to Earnings. Enter: Price to Gross Profit. Gross profit is cool, because everything is stripped away except revenue and cost of goods sold. If the company’s gross margins are good, it can probably achieve profitability with scale. For “unprofitable” companies, gross profit paints a picture of how profitable they could become.

But the problem with gross profit is that it still includes some expenses. What if we take away those expenses, and only value companies on their revenues? Sure, gross margins probably seem important. A software company with next-to-no costs may have 80% gross margins, and it can scale revenue at little additional expense. Meanwhile, an automotive manufacturer with high costs and 18% gross margins will incur a lot of additional expenses as it expands production. Let’s not fuss over the details though. We now value companies on Price to Sales, or valuation divided by revenue.

But the problem with Price to Sales is that you need revenue. But some companies haven’t sold anything yet! So how do we value that? Obviously we don’t want to include any expenses, because those can paint a negative picture. But we don’t have any revenue either. But now, we have a new P/S ratio: Price to Story.

In February, Morgan Housel wrote an excellent piece about the value of story telling.

I particularly liked this quote:

“The common stories are 1+1=2. We get it, they make sense. But the good stories are about 1+1=3.” That’s leverage.

1+1=3 are the stories that take good fundamentals (profitable, rapidly growing EV company), a good environment (favorable government policies) and a fantastic narrator (Elon Musk). Tesla is vintage 1+1=3.

But the best stories? They don’t have any fundamentals at all. They are like the last five Fast & Furious movies, where the plot is so ridiculous you can’t help but be entertained. Vin Diesel would love the electric vehicle market.

Tesla IPO’d at a $1.7 billion valuation with 2400 cars delivered in 2010, which was probably overvalued. Fast forward to 2019, where Tesla was worth $40 billion on 367,500 deliveries, which was probably overvalued. And now, Tesla is worth about $1 trillion, which is probably overvalued.

Rivian, a company that has delivered 0 vehicles, or 2400 less than Tesla in 2010, is worth $100 billion at its IPO, which is more than 50x Tesla in 2010. Rivian has also sold 367,500 less vehicles than Tesla in 2019, but it’s worth more than 2x Tesla in 2019. You read that correctly. Right now, Rivian is worth 2x more than Tesla was exactly two years ago. Without selling a single vehicle.

Is it overvalued? I don’t think so! In fact, sell side analysts have been largely bullish. Morgan Stanley analyst Adam Jonas gave a $147 price target, or ~$126 billion market cap, for Rivian, a company that has sold zero vehicles, based on 2030 projections. We know that 10 year sell-side forecasts are 100% accurate, because you never have unforeseen circumstances such as… a supply chain crunch? A pandemic? Trillions of new capital injected to financial markets? Idk. 10 year sell-side projections certainly aren’t less reliable than your girlfriend’s horoscope.

No sector has benefited more from being valued on stories than the EV industry.

EV companies today can capture all of valuation upside that Tesla created, without actually having to sell any vehicles. It’s great for investors as well! For the cheap price of $100 billion, you too can invest in a company that hasn’t sold anything. Because it’s the next Tesla! Even though it’s worth twice as much as Tesla was the year it delivered 370k vehicles. Seems cheap, no?

This Price to Story thing works for a while. Until you start selling vehicles. Because as soon as you sell that first vehicle, you have a tangible metric to compare yourself to other companies. You can attach an infinity multiple to a story, because stories are subjective. You can’t attach an infinity multiple to sales, because sales are objective.

Tesla will likely sell more than one million cars next year. Rivian expected to sell 20,000 vehicles this year and 40,000 next year. Except now Rivian is pushing back deliveries until 2022.

This is probably a good thing tbh. The longer Rivian can go without selling a car, the longer is can be valued as a “story”.

Considering the delayed deliveries, I doubt Rivian hits that 40,000 target. But say Rivian does deliver 40,000 vehicles next year. Is it really worth $2.5 million per vehicle at a $100 billion valuation? On a million deliveries, Tesla is “only” worth $1 million per vehicle.

And we haven’t even talked about the OG from Detroit. Ford.

Morgan Stanley, the bank that gave Rivian a $147 price target ($126 billion market cap), expects Ford to sell 150,000 EVs next year. Ford is also worth more than $20 billion less than Rivian.

Are Rivian’s 40,000 potential deliveries worth more than Ford’s 150,000 likely deliveries? Are Rivian’s 40,000 potential deliveries worth more than Ford’s 150,000 likely deliveries… plus the millions of non-EVs that Ford will sell?

Idk.

That also raises the question, how much would Ford’s EV division be worth as a standalone entity? At least $300 billion, right? Honestly its a shame that Ford hasn’t spun off its EV division!

Or maybe, just maybe, some of these EV startups are a bit overvalued.

But Tesla has been called overvalued for a decade! How can you call these companies overvalued?

True! But… Tesla was worth half of Rivian’s current valuation while selling hundreds of thousands of vehicles. And Tesla has this guy named Elon Musk. You know, the dude who singlehandedly jumpstarted the EV revolution (after helping revolutionize payment systems) while simultaneously building the world’s first reusable rockets, developing brain implants to cure neurological disorders, digging tunnel networks under Vegas, and shitposting on Twitter 25x per day.

The CEO of your EV company probably isn’t able to do all of those things. So I guess I’m saying it’s okay to pay up for an EV company if the CEO is Tony Stark. (It also helps when you benefit from three years of multiples expansion.)

The Investor’s Dilemma

The newest class of investors has joined financial markets at a time where growth stocks go up, boomer stocks suck, investing in ideas can make you a millionaire, and no price is too high for quality.

However, markets change.

When valuations are sky-high, execution has to be perfect for you to breakeven. And if growth slows down at all? Have fun staying poor.

When valuations are at rock-bottom, every little thing that goes right can make you money. Story based valuations are great, but eventually you have to generate revenue. Sales based valuations are great, but eventually you have to turn a profit.

If you’re investing in stories, you better hope J.K. Rowling is the author.

Have a great Wednesday.

-Jack

I appreciate reader feedback, so if you enjoyed today’s piece, let me know with a like or comment at the bottom of this page!

Young Money is now an ad-free, reader-supported publication. This structure has created a better experience for both the reader and the writer, and it allows me to focus on producing good work instead of managing ad placements. In addition to helping support my newsletter, paid subscribers get access to additional content, including Q&As, book reviews, and more. If you’re a long-time reader who would like to further support Young Money, you can do so by clicking below. Thanks!